2020 Commercial Global Space Market, Part 2: Profitable, but Not Mature (Yet)

This is the second part of an earlier analysis. It is the longest part, just so you are fairly warned. I assess that while the industry has been busy and profitable during 2020, its activities and profits aren’t signs of a healthy “commercial” space sector. That’s still a fairy tale. But, there’s plenty of room for improvement and potentially moving closer to that aspiration.

Have a Happy New Year!

Profits, Before "New Space"

There are thriving businesses in the space industry, even though they don’t always appear as active as newer space companies. These businesses have been around for over a decade at least and are more profitable than the newest arrivals. For international readers, the next few parts will lean towards US-centric activities and history (but not all).

Based on old Space Foundation data, commercial telecommunications companies around the world (SES, Hughes, etc.) experienced revenue growth during the last fifteen years, from a little below $60 billion in 2005 to a high slightly above $127 billion in 2017. There has been a small dip down in the past few years.

That dip could turn to a slide, depending on how successful Starlink and OneWeb are with their LEO broadband efforts. But those telecommunications companies were and are making enough profits to invest in newer, more capable broadband satellites (which aren't ready for orbital deployment yet). Some are beginning to publicly fight back against Starlink's massive deployments (but not OneWeb's--perhaps because it's a UK company?).

Before SpaceX, commercial launch service providers (ULA, Arianespace), while slow, were profitable (they still are). The prices they commanded fell into at least two categories: unreasonably high and higher. The former price still attracted those telecommunications companies. The latter could be considered the necessary subsidies governments willingly paid to prop up a business that didn't launch very often. Less expensive offerings from Russia and China attempted inroads. ITAR conveniently locked China out of the launch service provider market for American companies using U.S. satellites.

Satellite manufacturers made money as well. Some commercial companies go into debt buying their satellites, which cost hundreds of millions of dollars. The slow pacing of manufacturing and launch allows those commercial companies time to slowly pay off those debts. As with launch, governments easily and readily paid more for similar satellite products and services.

They paid exponentially more for satellites with no commercial counterparts. These higher costs are certainly a form of subsidization, even when mission assurance costs are added in. But traditional satellite manufacturers may be facing a change as satellite factories from SpaceX and OneWeb offer astonishingly high output at low cost.

Note that at no time did these established space businesses worry about the costs in this industry. The largest example of this was ULA's nearly annual ratcheting up of launch costs for DoD satellites, but other space companies committed similar business decisions. They knew that the government would pay a higher price for their products and services.

Aside from the regular publication of outraged accountability and inspector general reports, the government appeared comfortable with the concept of paying a lot for space capability (even dubious efforts). The DoD in particular encouraged the cost hikes as it obscured pricing under the blanket of national security and other great-sounding rationales. The arrangements appeared very cozy.

To quote a line from certain video series: this is the way.

The Costs of Government Business

Government support comes with costs, exemplifying other reasons why the space industry is still in its infancy--market distortion and a lack of global standards/norms. It also killed innovation.

The former, market distortion, occurs when either NASA or the Department of Defense feels the need to protect or grow some part of the space industry (primarily for NASA’s or the DoD’s benefit). Near the end of “Government Space Budgets=Industry Priorities (Where’s Commercial?),” I highlighted that the money both civil and military organizations disseminate to the space industry isn’t necessarily a good thing--not if the goal is a vibrant and healthy commercial market:

The budget allocations help explain some of the things happening in the U.S. space sector today. Both NASA and the DoD have attempted to implement programs to develop and support commercial space. However, their narrow focuses and the monetary resources they throw at the sector, distort the market, no matter how well-intentioned their programs are. Government mandates drive their narrow focuses, which are no substitute for free markets. For example, the DoD is starting to use the rationale of protecting U.S. space commerce with its new Space Force. But space commerce needs to grow first.

But commercial space shouldn’t grow only because of government needs--those can really skew a company's offerings. NASA’s and the DoD’s big budgets are why startups such as Planet pursue those government-established focuses. There appears to be too much market distortion for the company to chase commercial customers alone. Even a more successful company, SpaceX, is pursuing government contracts and subsidies.

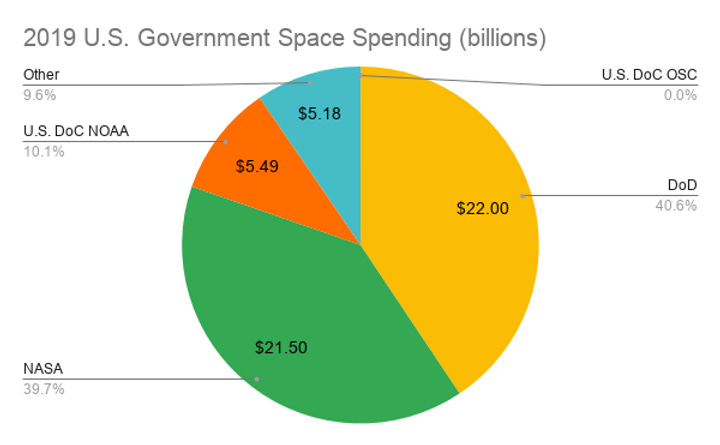

That analysis advocated that the Office of Space Commerce needs more support to become the commercial foil to NASA’s and the DoD’s influences. So long as most government spending goes to the military and NASA, the U.S. space marketplace will never have an opportunity to mature. Their mandates are too narrow. At the same time, OSC remains underfunded--in 2019, it received .003% of the nation's space budget. The imbalanced spending assures DoD and NASA dominance--odd for a nation that keeps promoting the commercial space industry.

As for global standards--their lack is another sign of the worldwide space sector’s immaturity. Implementing international space standards would increase profit-making opportunities while encouraging more businesses to become involved. To be clear, global rules of the road aren’t currently in place for the space business. In the U.S. alone, conflicting goals of military supremacy, national security, employment security, scientific advancement, exploration, commercial growth, and venture capitalist idealism make achieving such necessary baseline rules complicated.

Current market immaturity may surprise many out there, believing the space industry is resilient and robust. Discrete events and fickle investment trends back that belief (the safety net of government patronage plays into it as well). Going through those rationales point-by-point requires a separate analysis. I mention that tangent only to note that resiliency and robustness are unlikely in an industry with no rules of the road (and mostly kept afloat with government funding). Discussing that omission’s implications requires a short explanation. I will use an activity familiar to the world’s populations to demonstrate how rules of the road help: driving.

Autobahns and Achievable, Helpful Standards

Growing up in Germany and the United States, I became aware of similarities and differences in language, culture, architecture (500+-year-old farmhouses?), and signs. Especially when I earned my first driver’s license while still a teenager in Germany. My observation of the differences of driving there and then experiencing (currently) St. Petersburg residents’ notional adherence to driving law and signs is...well...let’s just say Florida’s drivers are foolishly fearless.

For those who don’t know, driving is a serious business in Germany. Knowing and obeying the laws and the signs along Germany’s roads are crucial to safety, important in a nation that allows drivers to exceed 100+ mph on freeways. Germans typically go through expensive driving schools. They also have the opportunity to learn to drive through mini-steps--first driving mofas, mopeds, and motorcycles. They know the rules and the signs, many of which are the same as the signs used in the U.S. But, some, including this sign, are probably not familiar to U.S. drivers:

That sign, from Germany’s autobahn, indicates no speed limit for the road beyond it. At least until the driver sees another speed limit sign later. And yes, I, too, wish these signs and rules existed in the U.S.--especially while driving through Kansas and the Dakotas. That sign indicates trust in drivers: confidence in their judgment and conviction in how German drivers abide by the rules of the road. Ironically, the rules allow freer and faster movement on the road. They are infrastructure.

These rules are dead easy to remember and keep billions of people from harm. Consider how many millions of American drivers are on the road, at any time, in almost any state (tired, wired, etc.). Out of the nearly 30 BILLION miles Americans drove in 2019, ~36,000 of them were killed in accidents. It’s a tiny, tragic number considering the high miles driven each year. Part of that success is that most drivers comply with standardized rules of the road the majority of the time—rules of the road work.

No matter what town or state in which a U.S. driver operates a vehicle, a stop sign looks the same. Traffic signals have the same meaning. Even sign colors tend to impart cues for drivers. These colors and shapes extend across the globe, and drivers know how to react to them. However, as the sign above shows, not all countries use the same signs.

Some rules are subtly different. For example, when I first drove in Germany, there was no turning right on a red light. But these rules change as people understand their utility. That German rule is changing now, because as Jeremy Clarkson once observed (in Miami of all places), "See this here! Look - he's turning right on a red light - that is America's only contribution to Western civilization." The similarity in rules allows visitors to drive in a law-abiding and safe manner--but some universal exceptions are adopted as time goes on.

At the risk of putting readers to sleep, here are a few examples describing how the rules of the road--nearly universally agreed-upon meanings--are beneficial.

They:

provide safety

are easily understood

are achievable

allow for flexibility in different environments

allow for judgment

apply to all drivers (yes, even police)

That last bullet is critical--if a small percentage of drivers follow different rules or don’t follow any, the resulting uncertainty makes the other benefits challenging to achieve. A license establishes with a government that a driver understands the rules of the road and agrees to comply to the best of that driver’s ability (St. Pete drivers appear to be the exception). The rules are an attempt to insert predictability in a system of individuals. Adherence to them is what allows insurance companies to flourish. The rules are just one part of a complicated system requiring roads, enforcement, maintenance, refueling, safety, etc.

Applying Rules of the Road to the Space Industry

From the outset, this is not a call for "controlling" the space sector. I believe these standards would minimize uncertainty, which would help the sector flourish. Also, I am not advocating clumsy attempts at centralizing standards from on high, such as witnessed with the National Space Council. These are just my observations on why the space industry isn't even close to maturity.

Again, the space industry doesn’t have anything remotely similar to the rules of the road. There isn’t even a “road” in the space industry. At least not yet. Treaties exist and some organizations, such as the ITU, attempt a very focused regulation on radio frequency use and allocations. The FCC uses its gatekeeper status to, weirdly, enforce some collision avoidance requirements. Some nonprofits have done a business in promoting “stewardship” of the space environment through addressing the orbital space debris issues (which, frankly, seem to manage the symptoms and not the root cause). It's all very scattershot.

To be clear, the words “space industry” typically describes all sorts of industries and activities concerning space. These can be satellite manufacturing and operations. It can encompass Earth observation. There’s also space launch and all the applications that rely on positioning, navigation, and timing infrastructure to consider. For everyone’s sanity, particularly mine, I’ll focus on satellite operations for my example.

If a satellite operator were to deploy a satellite, does it matter which nation the satellite launches from? What about the location of the satellite operator? Are the rules the same between an Indian operator and a Russian one? Does “safe” satellite operation mean different things to each nation?

What is the agreed-upon safety buffer between orbiting satellites in either country? If a Russian satellite violated the buffer-space surrounding an Indian satellite, what are the consequences of that violation? How would satellite “traffic” be monitored to ensure enforcement? What happens if a Chinese satellite no longer responds to commands, no matter what the operator does? Does it “stay on the side of the road” in orbit, or must someone call an orbital tow-truck? Must U.S. satellite operators comply with rules different from the ones guiding the Chinese?

Does asking those questions mean different rules are guiding the space activities of different nations? Yes--a high percentage--which means the other helpful parts of the rules are nearly impossible to achieve. There is uncertainty for how companies and nations react, even though they are in the same environment (Hi, SpaceX and ESA!). Similar questions can be asked of satellite design (designing in standard operational safety requirements--as is done with cars) or launch system design (emissions standards?). Each one of the questions I posed presents a business opportunity, indicating there is certainly growth potential.

This uncertainty, which encompasses more than satellite operations, is another reason I view the space industry as immature. Those who believe it’s too soon to implement these rules, does “too soon” indicate the global space industry is still too immature? And it’s interesting to note, for those who protest how these rules might compromise national security and defense, that the automotive industry's rules of the road appear to have had little impact on those essential missions. For those worried about standards impacting commercial interests, Ford, Volkswagen, Honda, etc. all figured out how to work within the guidelines and grow.

The good news is that there is growth potential for the space industry. The optimistic forecasts are potentially correct. They would be correct for reasons different from what they publicize, however.

Space is a business--at least it should be. The influences of nationalism, national security, and “grand projects on pedestals” in the space economy need to be rejected or minimized for businesses to flourish and not maintain the status quo. Like lunar mining executive orders and asteroid mining affirmations, those influences do nothing to establish realistic market conditions for commercial companies to become successful. In reality, only businesses can determine whether marketplace conditions present acceptable opportunities.

It’s clear much more cooperation and discussion needs to occur for those opportunities to become evident. Establishing standards provides a venue and purpose for nations and companies to work together. The obvious benefits from these discussions would augment commercial activity in space. These would contribute to creating a robust and resilient commercial space industry.

Comments ()