2Q21 Spacecraft Deployment Review

This short analysis calculates and examines the spacecraft deployed during the second quarter of 2021 (from 1 April-June 30). It is in addition to the 2Q21 Orbital Space Launch Review provided a few weeks ago. In other words, this is about what was put in orbit during 2Q21, while the Orbital Space Launch review covers the rocket systems that launched and deployed those things to orbit.

A lot of the data comes from Gunter’s Space Page and Space-Track.org. In addition, I track down more related information and use my knowledge to determine who is doing what from where.

That’s a Lot of Satellites

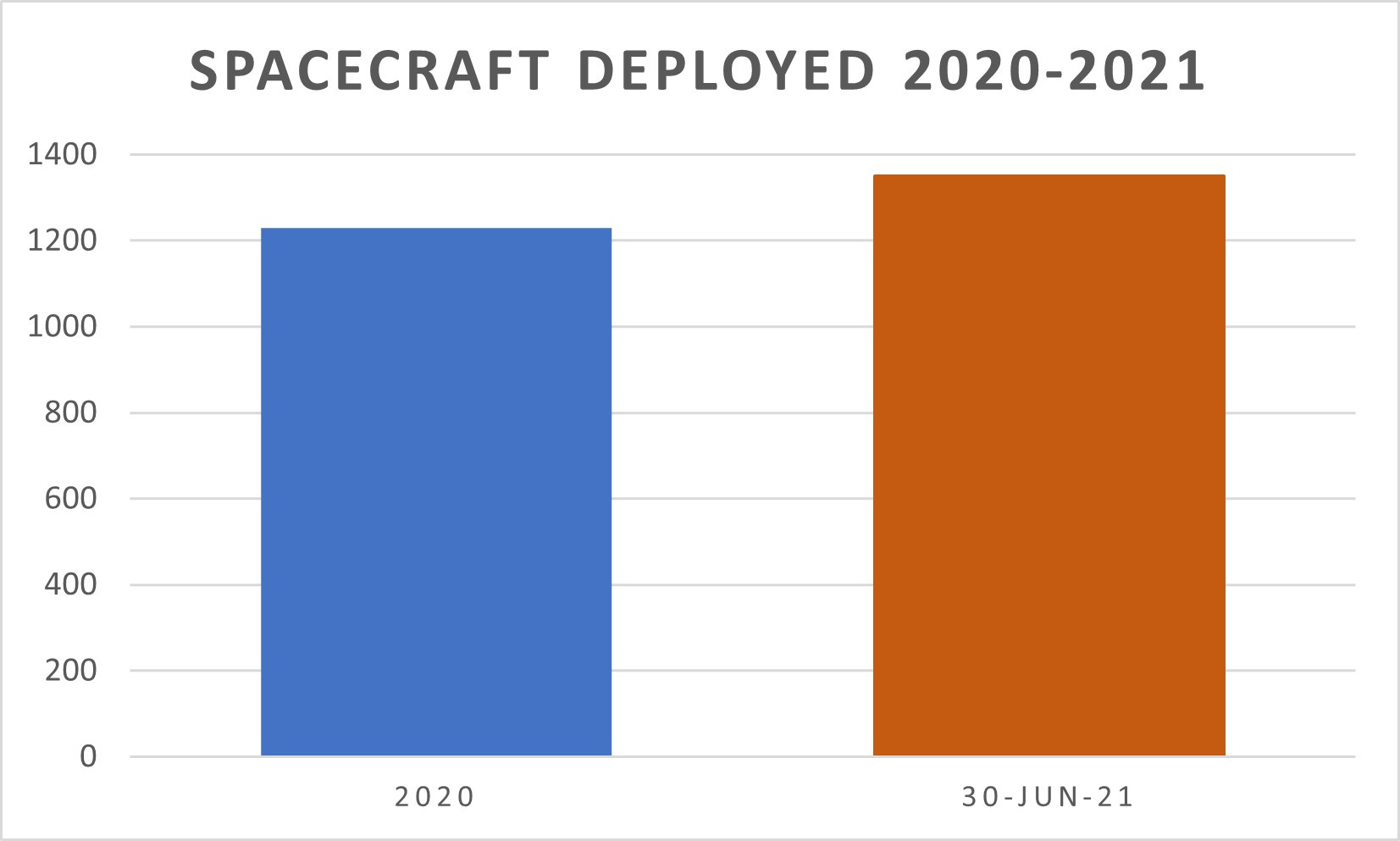

While the spacecraft deployed during the second quarter didn’t reach the 720 deployed during 1Q21, there were still a lot: 570. Add up both quarters, and all spacecraft deployed during 2021 have already exceeded the total spacecraft deployed during 2020. That’s 1350 for 2021 versus about 1230 during 2020.

2021 is already a record-breaking year for spacecraft deployments at mid-year.

Of course, SpaceX’s Starlink deployments are contributing significantly to the 2Q21. During the quarter, SpaceX deployed 355 Starlink satellites. Without SpaceX, a mere 215 spacecraft were deployed, which is still significant (not as high as 1Q21’s 290)--based on deployment histories earlier than 2019. OneWeb also contributed significantly, deploying 72 of its satellites during the same quarter.

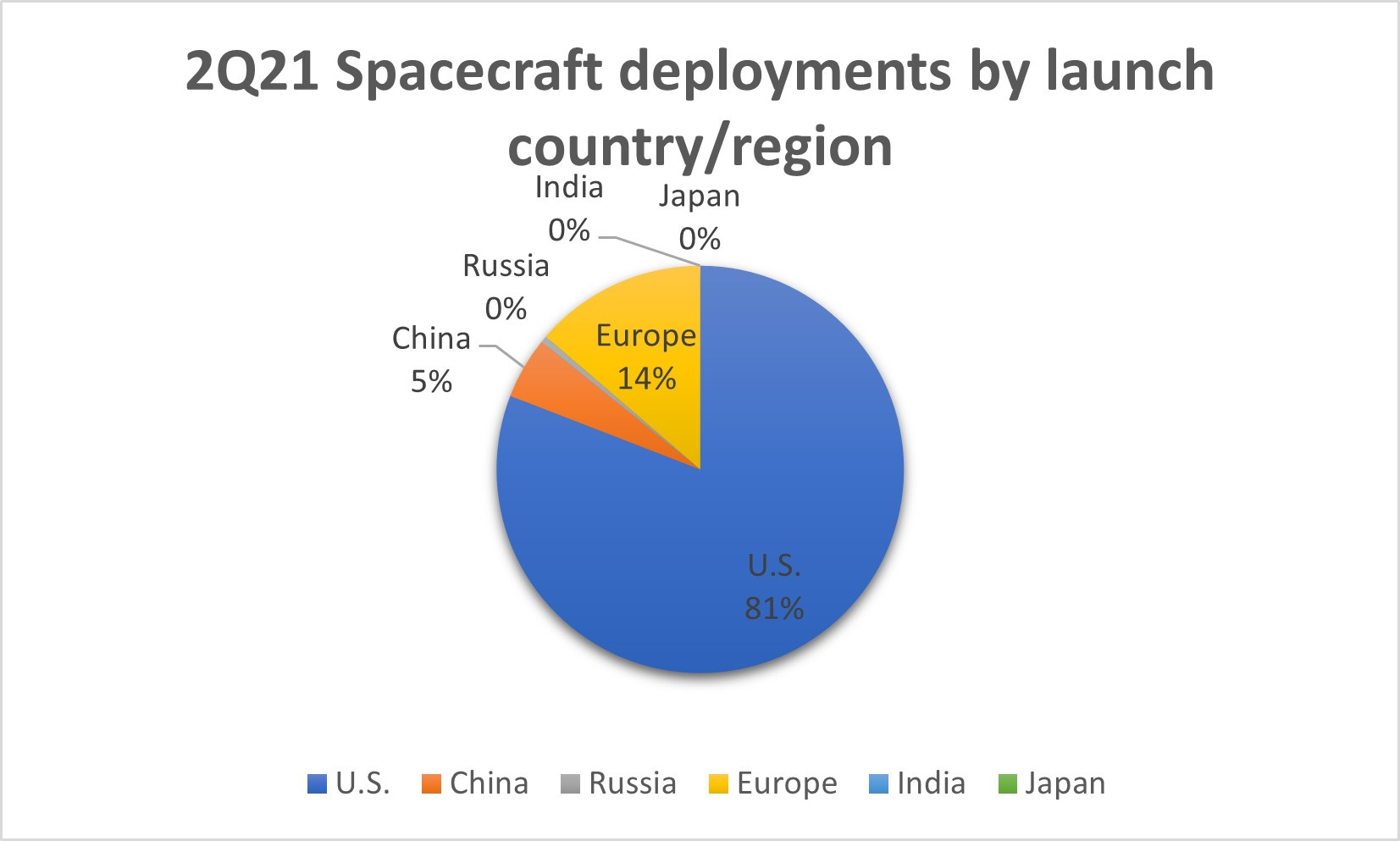

Russia used three rockets to launch three Russian spacecraft--that’s it. While the pie chart shows Russia with a 0% share, it’s more accurate to note it has 0.5 %.

Launch companies from three nations and Europe were responsible for deploying all spacecraft during 2Q21. U.S. launch providers were responsible for 81% of all spacecraft deployed in the second quarter. Except for Rocket Lab, all operational U.S. launch providers (ULA, SpaceX, Virgin Orbit, Northrop Grumman) launched spacecraft into orbit during the quarter. Europe, primarily because of Arianespace’s OneWeb launches out of Russia, had the second-highest share with 14%. China’s launch providers launch only Chinese satellites, gaining it a 5% share.

Neither India nor Japan launched anything during the second quarter.

While China’s deployments significantly increased from 1Q21, it appears to be an isolated market, with no foreign customers attracted to the nation’s launch service providers. The absence of foreign customers is despite supposed low launch prices. Compare this lack to SpaceX’s Transporter missions, which have attracted companies from many nations.

2Q21 Satellite Operator Breakdown

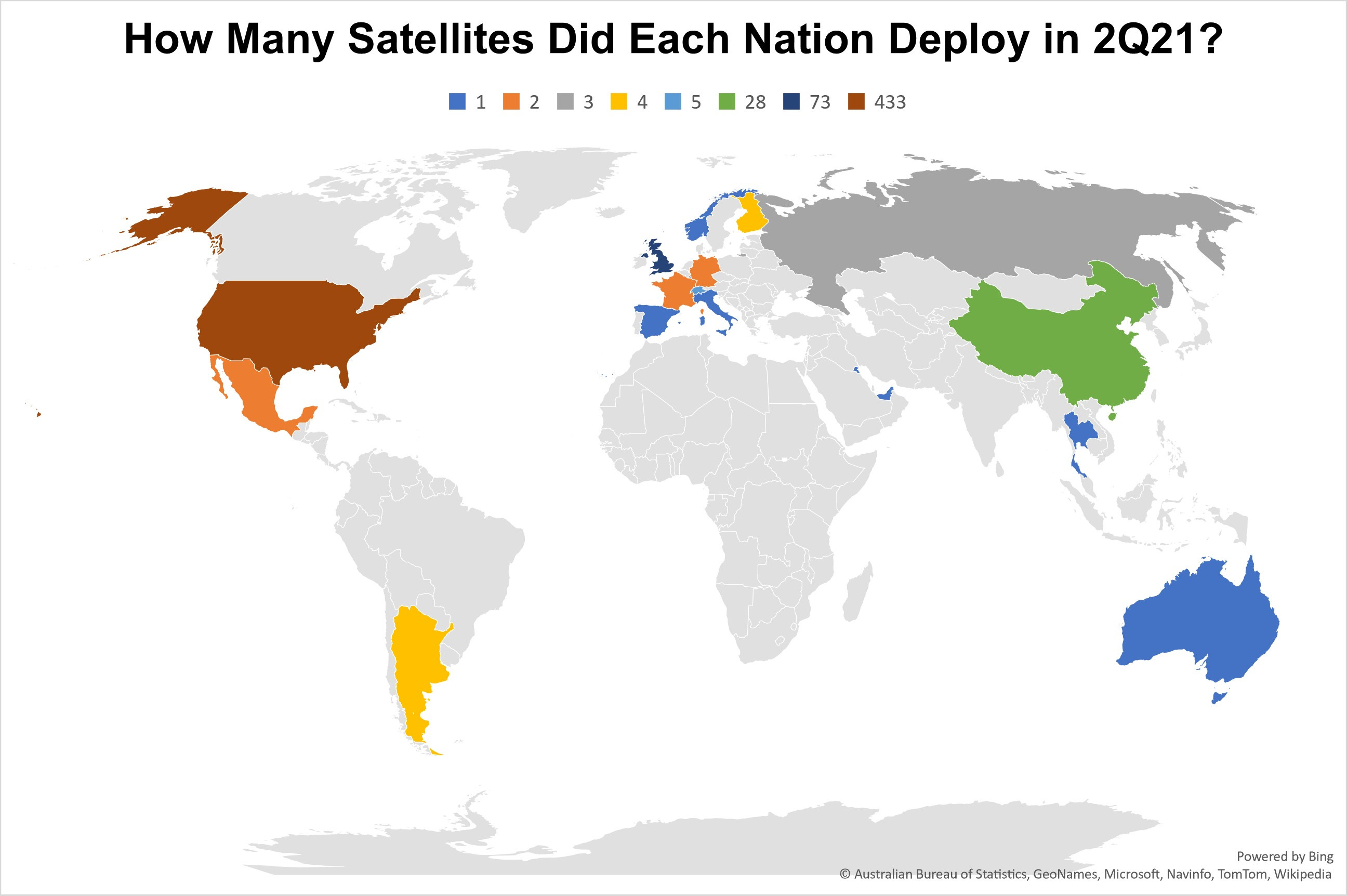

U.S. satellite operators deployed 433 spacecraft during 2Q21. Without SpaceX’s 355 Starlinks, U.S. operators are whittled down to 78 spacecraft deployments. The nation’s operators with the next highest number of satellites deployed were from the United Kingdom with 73. China’s satellite operators deployed 28.

Space operators from 20 nations deployed spacecraft into orbit in 2Q21, thirteen less than in 1Q21. Among the twenty, new operators from the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait deployed satellites. Forty nations have satellite operators that deployed satellites during the first half of 2021.

As far as companies with the most satellites deployed during 2Q21, U.S.-based SpaceX was the company with the most deployed satellites (355). OneWeb, a U.K. company, deployed the second-highest number of satellites--72. Finally, nanosat company Swarm Technologies (also from the U.S.) managed to deploy 29.

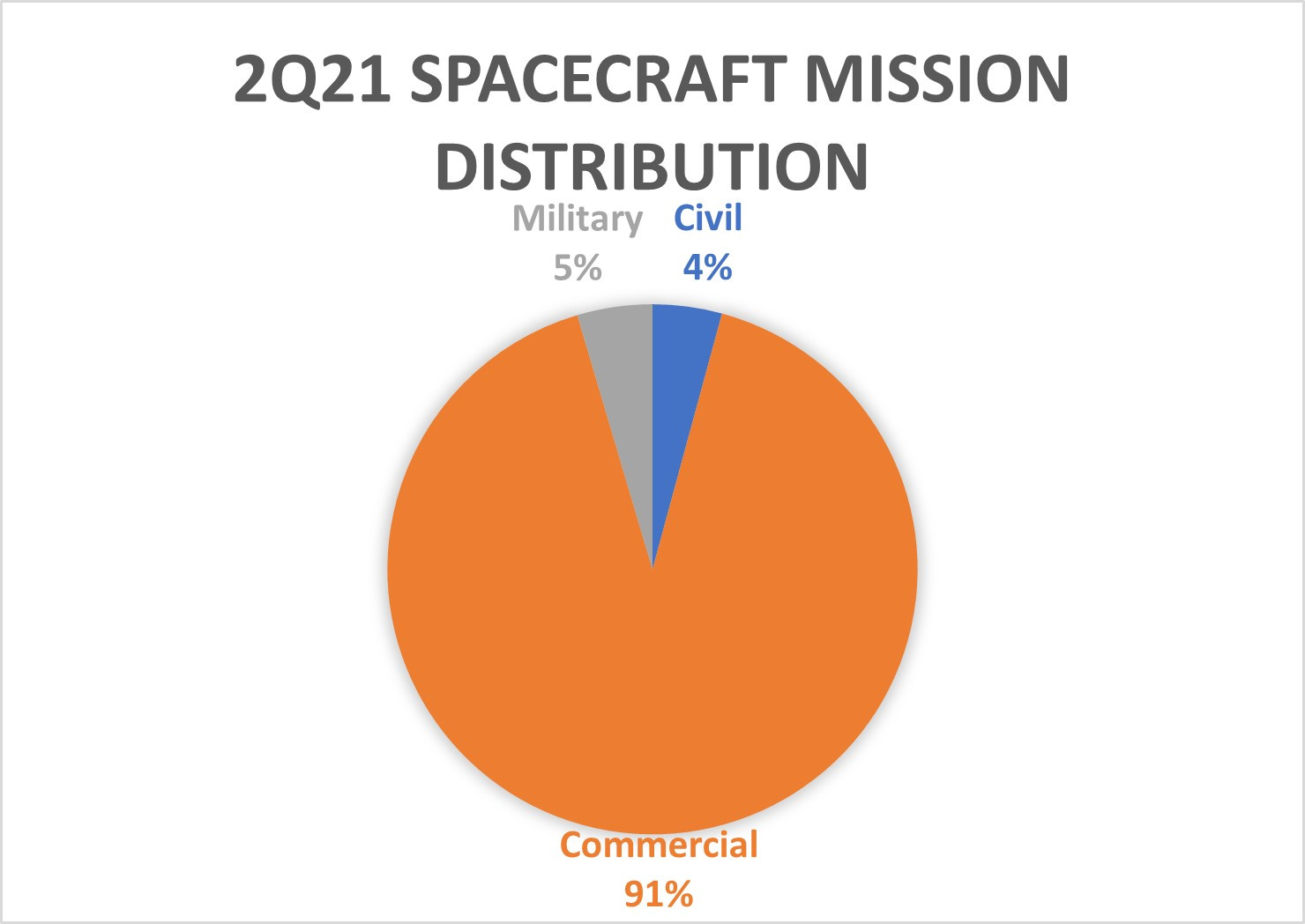

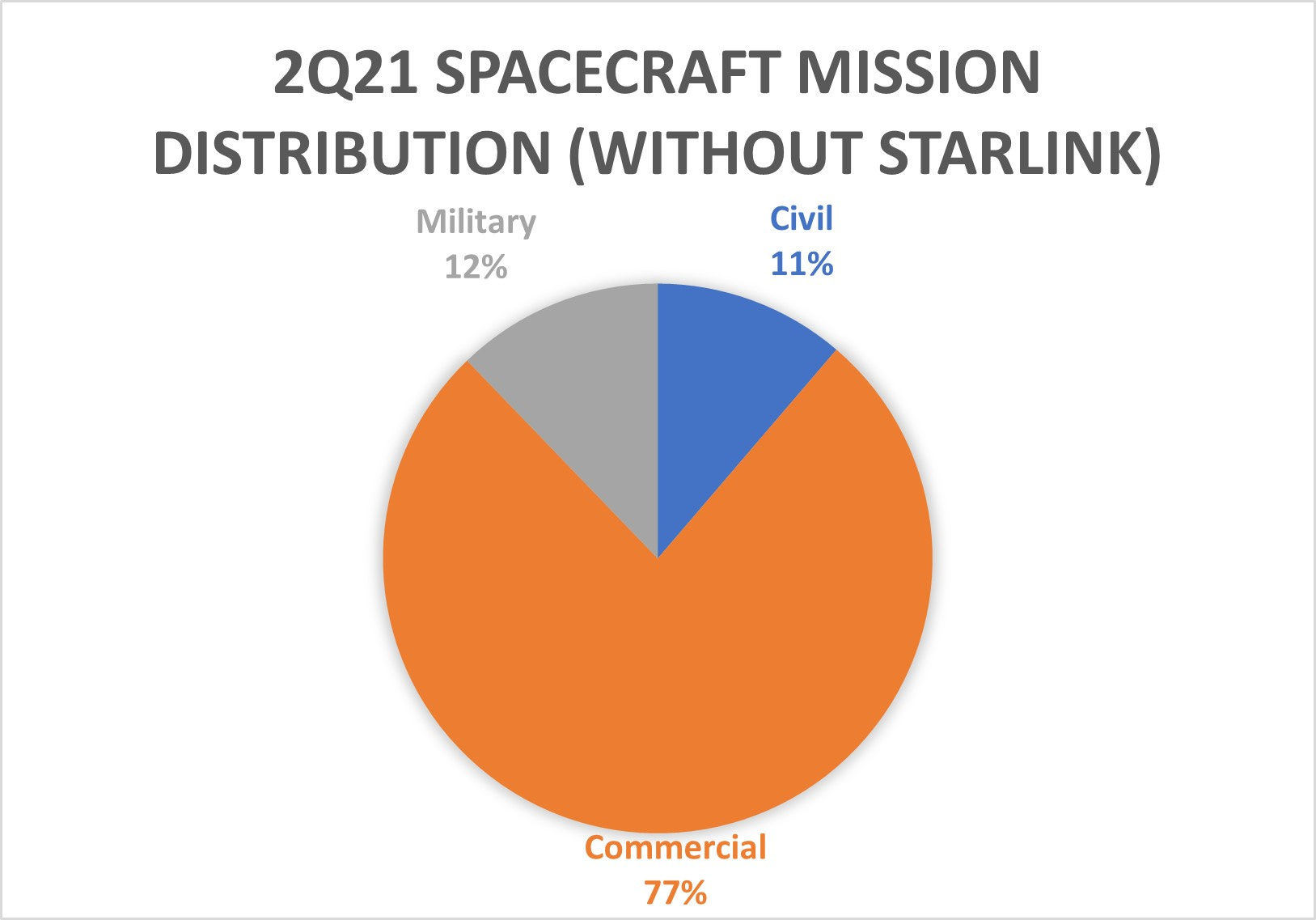

2Q21 Satellite Mission Breakdown

I am using very simplified definitions for the mission categories: civil, commercial, and military. The definitions are:

- Commercial: launches of satellites with a commercial purpose (profit is the priority)

- Civil: launches of satellites with a civil purpose (government-provided public services)

- Military: launches of satellites supporting/augmenting a government’s military

The share of deployed spacecraft serving each category breaks down like so:

The share of commercial satellite deployments grew from 1Q21’s 87% to 91% for 2Q21 (of 570 spacecraft). Subtracting the 355 Starlink satellites increases the share of military and civil spacecraft deployments.

However, commercial satellite deployments still took over three-quarters of all spacecraft deployments in 2Q21 (215). That’s an 11% increase from commercial spacecraft deployments in the previous quarter (66%).

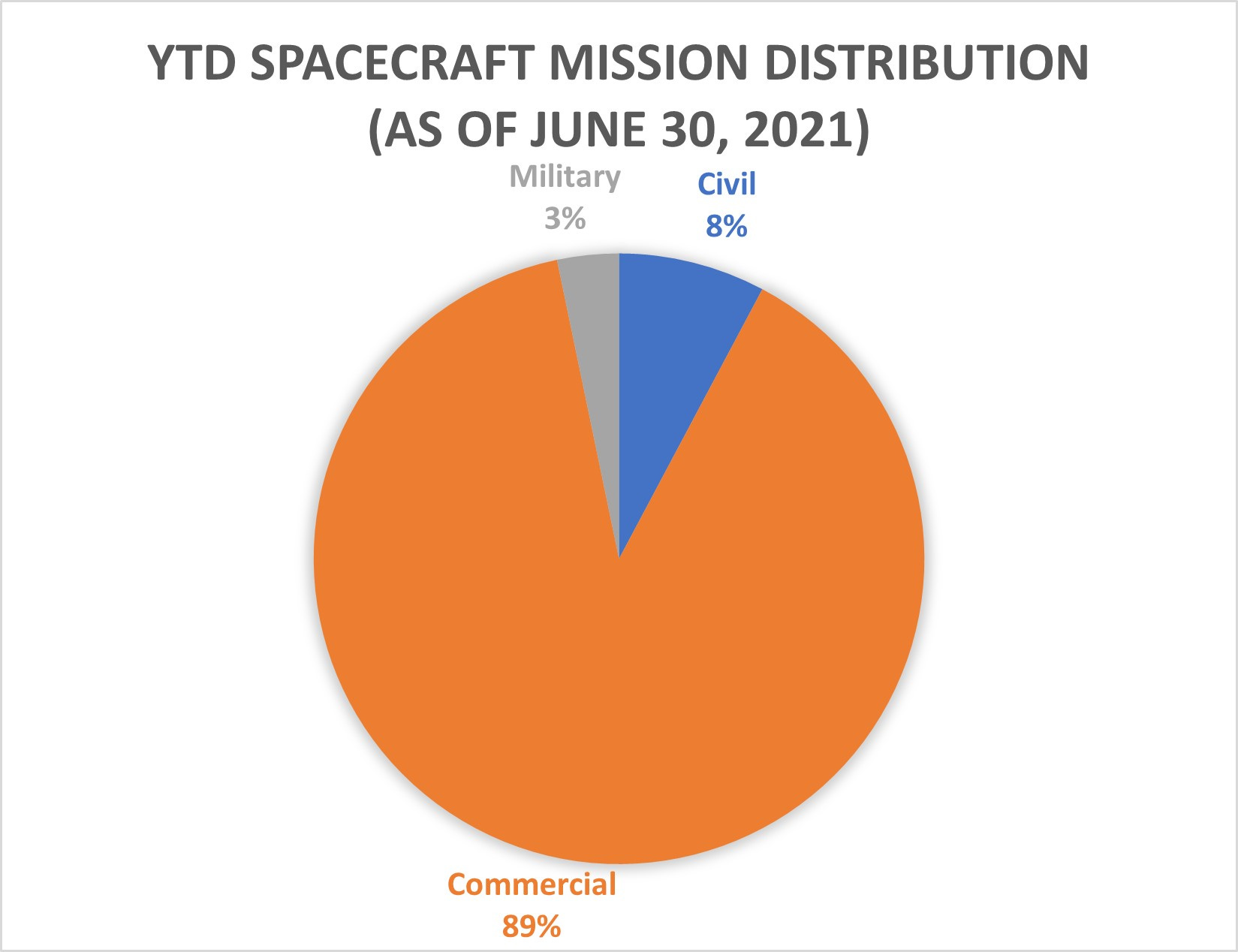

Year-To-Date (as of June 30, 2021)

As noted in the beginning, more spacecraft have been deployed during the first half of 2021 than at any other time in the space industry’s history. The number of spacecraft deployed during 2021 are already 100+ spacecraft over 2020’s record-breaking numbers.

More encouragingly appears to be the trend of actual commercial satellite deployments outnumbering all other deployments. It’s growing even without Starlink’s numbers to bolster it. Commercial mission dominance used to not to be the case not that long ago. It’s helpful, however, to keep in mind that while those commercial satellite deployments have increased, they are more in line with what the actual value of the market is versus what government and military agencies are injecting into the system (i.e., more money than sense).

So, while the distributions (including Starlink) for 2021 so far show significant commercial share, deployment-wise, a single military satellite (from SBIRS, for example) may have more contract value to manufacture and launch than the commercial sector’s entire value. But that difference is not stopping the growth.

Other Observations

Based on the data coming from the previous launch and this orbital deployment review:

China and Russia are not growing out.

China seems to be relying on indigenous launches indicates its services aren’t desirable or acceptable to the rest of the world. Its satellite operators are in a similar position. There’s a continuous feed of “news” chatting up the commercial growth of China’s launch and satellite industry. And, yes, China is busy with launches and satellite deployments during the first half of 2021. But government and military missions took a significant share (86%) of the nation’s satellite deployments during that span. It was even more lopsided for its launches.

Russia doesn’t appear to be recovering. For the first half of 2021, the nation has deployed nine spacecraft, with about two-thirds of them dedicated to ISS missions. The relative small-scale activity may be due to a combination of factors: aggressive competition, isolationist politics, reliance on former achievements, etc. But it’s saddening, in a way, to see Russia not using its knowledge and expertise to keep it from fading away.

As an aside regarding both of these nation’s purported offensive space activities: A question I have regarding these comparatively paltry overall space activities is about the narrative that each one is building up assets to defeat satellites operated by free nations. The data in these reviews indicate hundreds to thousands of spacecraft orbiting the Earth, operated by different companies, and using a multiplicity of ground systems. Is it even logistically likely to deny the use of every single satellite (unless they make it harder on themselves, too)? I doubt it.

SpaceX’s Smallsat Rideshare Program is a Godsend for Smallsat Operators.

Smallsat operators are increasingly taking advantage of SpaceX’s Smallsat Rideshare program with its $5,000/kg pricing. These smallsat operators come from various nations and have businesses across the spectrum--still generally focused on Earth observation. However, there are increased numbers in synthetic aperture radar and internet of things operators, satellite outfitters, satellite deployers, and more who launched on a SpaceX Falcon 9.

Related--there are a lot of Operational Smallsat Companies Out there.

A lot of them are manufactured and operated by companies in the United States. The high share is certainly very one-sided today, but that share indicates plenty of opportunities for other companies in other nations to dive in. It turns out that smallsats can be more than “debris” or “junk” sats.

However, and tying in with SpaceX’s Rideshare program, launch appears to be the bottleneck for smallsat operators. Each operational smallsat launch service provider appears to have full manifests, despite SpaceX’s offerings. It’s not helped by slow to nonexistent Indian launches of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle. Arianespace’s and Rocket Lab’s challenges with their smallsat launch vehicles are also slowing things down. And while China has plenty of smallsat launch capability, it’s only launching Chinese satellites.

But the upshot appears to be there is an appetite for smallsat launch priced around $25,000-$30,000 per kg. The price acceptance and appetite is good news for those companies that are only smallsat launch press-release puppets today, should they decide to become operational.

This year continues to be an exciting year for the space industry.

Comments ()