A Grudging Look at National Space Policy

I don’t write about space policy.

First, there are already plenty of people out there who make a career out of writing about the topic. Bless them--it keeps them out of the rest of humanity’s way. Give them their version of a box of crayons and a blank piece of paper, and let them go to town. The refrigerator door that is the internet has plenty of room to display their scribblings proudly.

Also, I find space policy incredibly dull. I shouldn’t, but...here we are. Policy is to the space industry and reality as organizational mission statements are to employees--at best, mostly aspirational and irrelevant. At worst, it gets in the way, which is why I won’t write about the intricacies of the 2020 National Space Policy of the United States of America. It was released this month.

What I will do, however, is make a few observations about the document, especially in comparison with 2010’s NSP. The focus here is on the “Commercial Space Guidelines” segment (page 10 in the 2010 document, page 20 in 2020). Considering how much the current administration has discussed space commerce (more than its predecessors), the guidelines surrounding the commercial space industry in the U.S. should have changed a bit.

Commercial Guidelines

But they haven’t. In the 2010 policy, there are 12 bullets for how U.S. agencies’ heads will help promote “a Robust Commercial Space Industry.” Fifteen bullets make up the 2020 policy guidelines. Most of the guidelines are remarkably similar between the two documents, with obvious wordsmithing to make it look like taxpayer money paid for something in 2020’s version. With ten years of industry changes and the remarkable amount of publicity given to the U.S. commercial space industry from the current administration, shouldn’t there be something more? Shouldn’t the U.S. government have learned a few things during the past decade? Apparently not.

As one would expect from the current administration, some amended bullets imbue a protectionist flavor. These bullets specify U.S. commercial space companies’ selection rather than an (apparently non-existent) open space market providing the best capabilities and services. To be sure, there’s always an out in these guidelines, such as the words “maximum practical extent.” However, it’s reasonable to assume most heads of agencies will choose the painless route--until the policy changes again. Also, national security has been added to a few bullets as reasons why things might not be available or denied. This national security deference seems at odds for an administration hot on space commerce.

One of the amended bullets contains an attempt to combat China’s space technology acquisition activities (the bullet doesn’t specifically reference China). There have been a few stories about China’s government using front companies to invest in needy U.S. startups and companies and then shuttling their technology back to China. The additional words fit neatly with the current administration’s focus on China as its bogeyman.

The three added bullets deal with:

- getting local and state governments to build up a “technically skilled workforce.”

- making technologies created through Federal research and development available to industry

- helping grow U.S. commercial human space activities in LEO and beyond

Focusing on 1 and 3

The first new bullet is the U.S government kowtowing to U.S. companies’ lamentations of a lack of a homegrown technically skilled workforce, which they’ve been pushing for years. Plus, it sounds great to the public and the government. The bullet’s wording and the recent history of all the states’ fumbling efforts against the pandemic indicate results for this will be the same: ineffective.

Even if it was effective, the--admittedly cynical--reality is that those companies would like the government to encourage more young minds to go into engineering to produce a cheap labor pool. Once the students graduated, then those space companies could hire and underpay the newly-minted grads before a Google or a Facebook snapped up the talented ones to pay them the actual value of their work--instead of what the space companies would like to pay. The problem is, this growth of a “technically skilled workforce” doesn’t guarantee those STEM grads will go into the space industry. It may mean an exponential increase in smartphone applications.

Bullet three doesn’t mean much, either, as “helping” to grow commercial human space activities probably refers to NASA wasting billions more on the Space Launch System and Orion. Part of this is to appease lawmakers so that NASA can continue to fund, piecemeal, more promising and productive companies. Since there are no other changes in the remaining bullets, this goal is perhaps in place to give the primes some hope for the U.S. government implementing a plan for the “CIS-Lunar economy.”

Both bullets seem Kool-Aid fueled, with no real guidance for actually growing a thriving commercial space sector. And there’s nothing within any of the guidelines indicating fundamental changes to the National Space Policy. But since I’m not a policy wonk, I might have missed something.

Commerce in the Corner

There is no mention of the U.S. Department of Commerce (DoC) in the fifteen commercial space guidelines. However, the Secretary of Commerce is mentioned in two new subsections after them--”Mission Authorization of Novel Activities” and Foster the Development of Space Collision Warning Measures.” Both describe new activities the DoC will accomplish to “help” commercial space businesses. Also, the DoC is mentioned in the Civil Space guidelines, too--but we’re not focusing on that.

The first is reactive and a catch-all task--if someone in the U.S. commercial space industry is doing something different and unexpected, then figure out how to regulate it. DoC is expected to do that as minimally burdensome as possible (but it still would be burdensome).

The second activity falls in line with earlier administration policy pronouncements about DoC’s space situational/space domain awareness responsibilities. The responsibilities outlined in this activity spell out what’s required for the DoC to become the space collision warning subject matter expert.

Both activities might have more immediate impacts--if the DoC were allocated a budget commensurate for accomplishing these tasks. But its “space budget” is laughably microscopic. In “Space Commerce and Earth Observation,” I wrote about this budget problem:

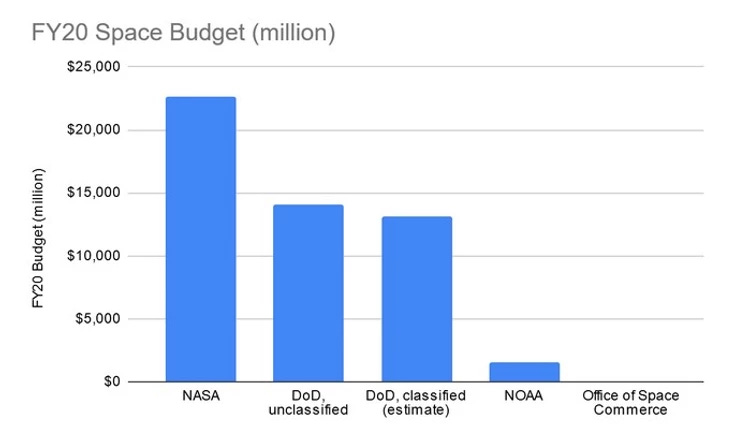

Last year, the Office of Space Commerce was granted more money for FY20 than it requested--$6.4 million--equaling an astonishing $10 million. "Astonishing," because that is such a paltry amount in the world of U.S. government space spending. NASA, for instance, received $22.6 BILLION for FY20. The unclassified DoD budget in FY20 for space programs was $14.1 billion (likely to be an estimated 93% more than that when including classified programs). The DoC's very own National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) received $1.5 billion for space programs.

So, $10 million isn't much. It doesn't even register on the space budget chart below:

A few managers and orbital analysts could blow that budget. But maybe Commerce gets more serious about space commerce next year.

A few examples of being serious, which would have been nice to see in the policy:

- Serious discussions/actions to get rid of International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)

- Ditto for national security influence:

- National security needs to step back for strong commercial space market growth.

- Space situational awareness means know precisely where ALL objects are in the space around the Earth--none of this orbital-element obscuration silliness.

- Classification rules should be examined with a “do no harm” eye on commercial market growth.

- A one-stop-shop that determines all rules and regulations for commercial space operations (including commensurate funding)

- No need to go to NOAA for one thing, the FAA for another, the USGS, etc.

Perhaps those ideas and others are more detail-oriented than what space policy requires--more suited for regulations, instead. But the foundational policy is uninspired, copying most of the old policy. The upshot is that for U.S. commercial space companies, the “new” national space policy will cause no changes. The policy’s non-progressiveness could be considered a good thing unless fostering the space market’s growth is a goal.

Comments ()