Charts, Perceptions, Reality: China’s Rockets

Context Matters! (Chart Design, Too)

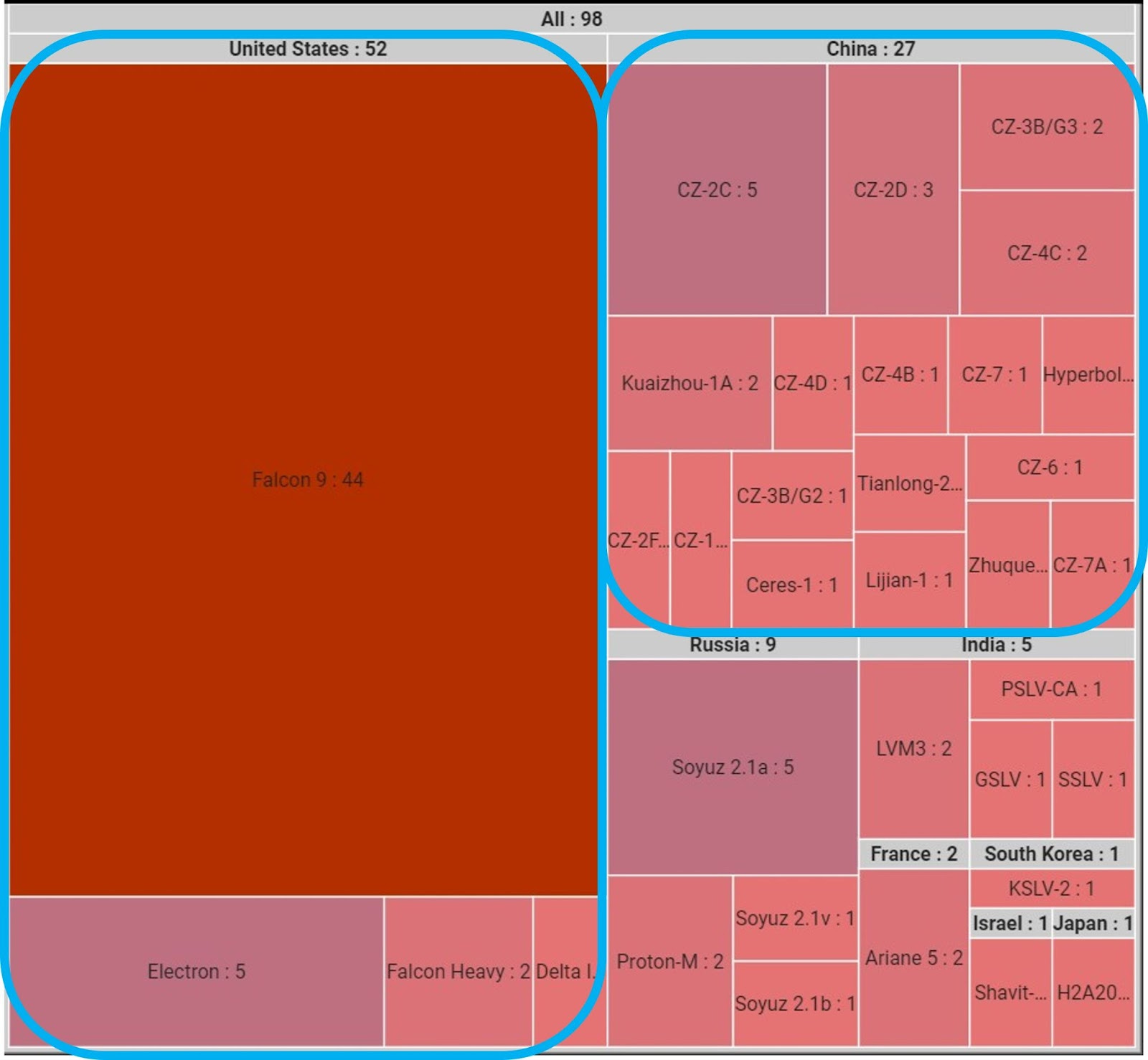

This analysis starts with a chart I used a few weeks ago in another of my analyses: Does Adding One More Competitor Help National Security Space Launch? I used the chart to compare the sheer variety of rockets China’s launch service providers used in the first six and a half months of 2023 vs. the lack of variety used by U.S. launch service providers. The chart looked like so:

Orbital Launches, Jan-(mid)July 2023

When I posted the above treemap, I thought the data presented was pretty obvious. And it was, in context with my article. It showed the rockets launched in 2023 so far, with the number displaying how many times they were launched. And while that information is useful, it wasn’t the point. The point was the variety of launch vehicles operational in China and to provoke some thought about why the inventory of U.S. launch vehicles isn’t as varied. My article’s words and the chart title helped establish the treemap's point.

Then, a reporter, Ars Technica’s Eric Berger, saw it and thought the treemap was interesting enough to push out on Twitter (or whatever the heck it’s called today).

To be absolutely clear, I have no problem that Eric did this. No matter who does it, it is always cool to see my writing and work re-tweeted. However, the image Eric posted left out the title and, of course, the text explaining the treemap, which resulted in confusion.

It doesn’t help that Twitter isn’t a great place for context. Naturally, people on Twitter asked about the numbers next to the rocket names (what were they and what they meant). They saw the dominance of SpaceX’s Falcon 9, the U.S. “beating” China, etc. Of course, no one asked anything close to something like: why are the inventory differences so dramatic? Or if they did, it got lost in all the other comments.

So, perhaps the primary lesson is I need to design my charts better so that the context isn’t quite so left out. However, seeing others’ takes on the treemap was interesting–it functioned almost like a Rorschach Test.

Some stated that China’s launch providers are somehow “cheating” using rockets with solid rocket motors. Others implied that reliance on rockets using solid rocket motors only is somehow less sophisticated than, say, Astra’s rockets. And more seemed to think that solid rocket motors solely powered the Chinese rockets in the treemap.

The other sentiment seemed to be that any rocket with the CZ appellation meant many or all were the same–just configured differently using (you guessed it) rocket motors. These inaccurate assumptions may have logical reasons for inaccuracy (language differences, national security, etc.). Much of it can be attributed to the echo chamber that is Twitter, with commenters falling prey to that. That’s the nature of that site. But Twitter is still useful for generating adult conversations, which is why I use it.

At the risk of moving into “Old Man Explains at Cloud” mode, it might be helpful to look at some of China’s rocket launch inventory cursorily and attempt to explain why such comments are not entirely accurate.

For those wondering about my sources, China’s companies and agencies are understandably proud of their rockets. So, the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT) and Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST) have much information regarding CZ rockets and a few others. And, just like startups in the U.S. and Europe, China’s space launch entrepreneurs have websites chock full of information about their rockets. However, unlike their U.S. and European counterparts, quite a few of their rockets have flown to orbit.

SRMs–A Solid Option

China has A LOT of solid rocket motor (SRM) rockets–primarily in the form of short-, medium-, and intermediate-range missiles, typically mounted on mobile launch rigs. There is a shelf-life for that kind of rocket, meaning that China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) either destroys those missiles or finds another use. For example, the Kuaizhou-1A is supposed to be based on the DF-21/CSS-5 (DongFeng) medium-range missile. It even launches from a mobile launcher and is operated by PLA personnel.

So, there are some grounds for believing that, since China’s military has so many SRM-based missiles sitting around, some have been in inventory for so long that a few are becoming unreliable for military purposes. Using those old SRMs for space launches in smallsat launch vehicles rather than destroying them makes a certain amount of sense. Plus, those launch vehicles are useful for deploying smallsats to orbit. It’s smart and not wasteful.

There’s some history in the U.S. of doing something similar. A few Orbital Sciences launch vehicles were derived from Minuteman and Peacekeeper intercontinental ballistic missiles. Orbital Sciences used SRM-powered rockets such as the Pegasus and Minotaur(s) for orbital launches, although the payload masses these systems could lift were quite humble.

For the most part, the Chinese SRM-powered rockets also lift small masses to orbit–averaging an upmass capability of 300 kg. But those rockets don’t make up most of China’s launches, despite what some people believe.

As noted earlier, the Kuaizhou-1A uses SRMs only. Others on that treemap–Hyperbola-1, Lijian-1, and CZ-11–also do that. The Ceres-1's first three stages are SRMs. So that’s five out of 18 rocket types that rely only on SRMs for launch–a little over a quarter of rocket types launched from China during the first 6.5 months of 2023.

However, other smallsat launchers in China are using alternative propellants, too, indicating some willingness from that country’s launch operators to experiment and innovate, not just rely on existing SRMs.—both examples launched in the first half of 2023. The Tianlong-2 is a rocket that uses coal-based kerosene propellant. Zhuque-2 was widely advertised to be the first operational orbital rocket using methane. Whether either propellant alternative sticks remains to be seen, but methane certainly seems to have a future considering its inclusion in Blue Origin’s and SpaceX’s engine development.

The Same Rocket–with SRMs?

Are they the same rocket?

Perhaps people get this impression of China’s larger rocket inventory because ULA did something similar with its Atlas and Delta rockets. They were essentially the same booster core in either family but attached SRMs to provide more oomph to orbit without compromising capabilities too much. We saw this with 401 through 551 for the Atlas and M+ with the Delta IV. The visual result in a treemap makes it appear as if a variety of rockets exists, even though the core is the same.

China’s launch services similarly append SRMs to their CZ rockets, but not to the degree ULA did. Evidence of potential similarities comes from CALT’s graphic of its rockets on its website:

The CZ-3 family is based on the CZ-2C and adds a stage, so there is a familial tie between the two rocket types. However, other CZ rockets, such as the 5, 7, 8, and 11, are very different from each other. Some use different propellants, with the CZ-11 dispensing with liquid propellants altogether. To make things more confusing, CALT isn’t the only one manufacturing CZ rockets. SAST also builds a few, and they are also different.

SAST has built China's second-most-used rocket during the past 4.5 years–the CZ-4B (CALT’s CZ-2C launches the most). It also produces the CZ-2D and CZ-6 (a smallsat launcher). While there are some reasons to initially think these rockets all have the same core (ULA’s example, the CZ-2 and CZ-3 connection), CALT and SAST produce more current operational rocket types than all other nations–combined. They seem willing to try different propellants and configurations, and are even experimenting with reusability (the CZ-9).

And that’s before adding in the smallsat launch startups.

Merely Rockets

To be clear, nothing in the data suggests China’s rocket launch companies are using any rockets that have superior technology to any other nation on Earth. Their current inventories basically work as those operating in other countries. It is interesting that there is such a large inventory of rocket types. And despite that large inventory and four spaceports, all of China’s launch providers combined aren’t able to come close to SpaceX’s Falcon 9 launch activities in 2023 (yet).

Some data suggest that the large inventory exists because China’s launch services must launch more rockets more often. And that’s because most can’t lift more than 4500 kg to orbit.

However, and unsurprisingly, because there’s such a variety of rockets to choose from, a few can lift almost double that 4500 kg, up to 23000 kg. They aren’t launched near as often as a Falcon 9.

In the end, China’s launch service providers have much to offer the world. But they don’t provide any of it to the world. Part of this might be that China has enough customers to keep its industry moving. A vast majority of launches from that nation are for Chinese space operators. At the same time, there is that trust issue that China needs to address if it ever wants more countries to use its launch services commercially.

But so long as that dynamic exists, launch operators from other nations probably don’t need to worry too much.

Comments ()