Does Adding One More Competitor Help National Security Space Launch?

Painted Into a Corner

According to a few of the space-related news stories from this last week, the U.S. Department of Defense seems to realize that there is a problem with its National Security Space Launch Phase 3 Lane 2 (Lane 2 from here on out) rocket acquisition contract–it only allows for two competitors. The latest reporting shows the DoD has rethought this concept and decided to accept more risk (in acquisitions terms) by now seeking three competitors in Lane 2 instead of two.

According to that story, a program manager provided the following hopefulness for the change in the DoD’s usual corporate-speak:

“We are confident that this approach will secure launch capacity, enable supply chain stability, increase our resiliency through alternate launch sites and streamlined integration timelines, and enhance affordability for the most stressing National Security Space missions.”

When the U.S. Space Force first put out its request for proposal draft in February 2023, it provided the following overview and goals for the updated NSSL program:

The United States Space Force (USSF) Space Systems Command, Assured Access to Space’s (SSC/AA) Operational Imperative is to deliver national security space capability to the warfighter to deter/defeat the pacing challenge. The NSSL Phase 3 approach to meet this Operational Imperative is to provide assured access to space to the integrated space architecture at affordable prices…

Theoretically, avoiding a launch monopoly is one of the DoD’s reasons for concocting overly complicated programs such as EELV and NSSL. But those programs pretend/hope the competition will somehow step up, which is unlikely without competition. Lane 2 won’t fix that awkward possibility—it’s based on the assumption there are at least two competitors. It’s not like NASA’s Commercial Cargo/Crew programs, which had competitors build rockets for its needs. There’s a chance that the DoD once again must rely on a single company for its launches. When that happened in the past, ULA’s launches got more expensive over time (page 11). It became so expensive that the DoD viewed the EELV program’s spending as “unsustainable.”

…Worse, the other half of its program [Lane 2] seems to embrace business as usual, which didn’t deter China in the past.

Hoping For the Competition

The pretense and hope remain for SpaceX’s competition to step up. Only, the U.S. military is pretending there are two other competitors instead of one. The DoD has already contracted with ULA for launches using its yet-to-be-launched Vulcan rocket. That seems like an uncharacteristically optimistic decision for the risk-averse USSF.

The latest ULA update indicates Vulcan will not launch until sometime before the end of 2023. The Vulcan must also conduct two successful launches for DoD certification before it can be “all in” on NSSL launches. In a period when one company conducts seven launches per month, using two launches as a basis for certification seems–unwise. That standard might have been considered a reasonable compromise for launch service providers that launched about once a month. However, even ULA anticipates launching double that average by 2025 (and not because of DoD launches).

ULA will probably–eventually–get Vulcan flying. However, the company’s CEO, Tory Bruno, gave a realistic warning to those expecting the road to Vulcan to be lined with yellow bricks while dancing and singing arm-in-arm along it. From another report regarding Blue Origin’s latest rocket engine failure:

“This is not unexpected,” Bruno said. “It won’t be the last. And there will be other components on the rocket that also fail acceptance testing.”

In other words, because Vulcan is new, there are going to be other problems that come forward during testing. As is the nature of new systems, other challenges will manifest after testing.

Another ULA challenge? Blue Origin has become the most significant ULA pain point in Vulcan’s development. The company’s development of the BE-4 engine for Vulcan has taken longer than anticipated. Also not great: Blue Origin is the other competitor the USSF’s updated Lane 2 is supposed to encourage. Except Blue Origin is an unproven launch operator with an unproven rocket (New Glenn) using an unproven engine with teething problems.

Moving Deck Chairs

It’s not as if the USSF minimizes risk, increasing Lane 2 from two to three competitors. The change gives the impression of dispersing the risk of relying on one company for USSF launches by adding another (that “secure launch capacity” line). Snaring Blue Origin with Lane 2 doesn’t do that. ULA relies on Blue Origin for its Vulcan engines. Blue Origin’s tortoise-like engine tribulations and development impact Vulcan and New Glenn launch vehicles, creating not a diversified launch ecosystem but one of dependence.

Although, it’s not clear what the USSF means by securing launch capacity. In many different meanings of that line, the USSF already has access to a rocket, the Falcon 9, that launches more frequently than ever. It accomplishes its tasks, in some cases exceeding the USSF’s requirements.

The Falcon 9 launches less expensively than rockets now and from any decade before its existence. The rocket is reliable, can be rapidly integrated with spacecraft payloads, has pretty high mass limits, and launches from three sites, averaging about seven monthly launches during the past six months. The Falcon 9 already answers the reasons for justifying adding competitors in Lane 2.

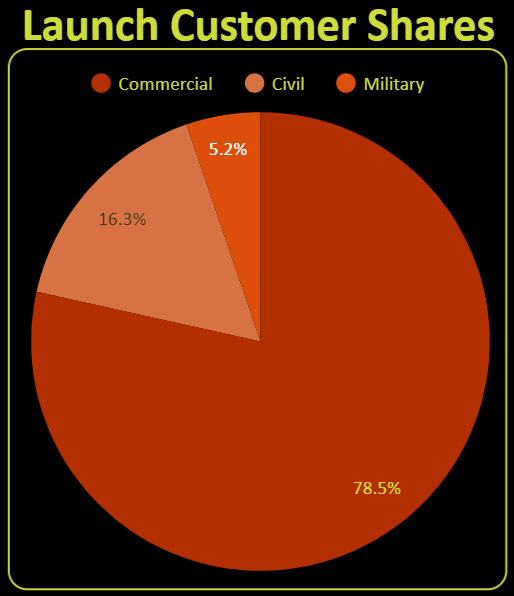

Even better, the Falcon 9 doesn’t appear to depend on the U.S. military for its launches and business (although SpaceX fought to get Falcon 9 accepted for DoD launches). From the beginning of 2019 through the middle of 2023, only 5% of Falcon 9’s launches were conducted to convey military spacecraft to orbit. Nearly 80% of Falcon 9 launches were from commercial missions (including Starlink).

2019 through mid-2023: Falcon 9

The Falcon 9 and SpaceX team have a record of excellence that should meet all of the DoD’s requirements (nearly–see Falcon Heavy). There is that little thing, however, that I’ve mentioned before–the dependence on SpaceX for nearly every military space mission. That’s perhaps an honest reason for increasing the competitors in Lane 2. The fact that ULA still hasn’t launched Vulcan probably incentivized the service to get Blue Origin in the picture, too. Only, as noted earlier–that’s still not great.

A Lessons Not Learned Moment for the DoD–Again!

The USSF is essentially trying to do what it’s done in the past for buying launches, despite the changes in the launch landscape. Maybe it should do something different since both attempts resulted in near-launch monopolies. It should look beyond its borders for examples of decreasing its dependence on a single rocket. Especially if the USSF wants to “secure launch capacity, enable supply chain stability, increase our resiliency through alternate launch sites and streamlined integration timelines, and enhance affordability for the most stressing National Security Space missions.”

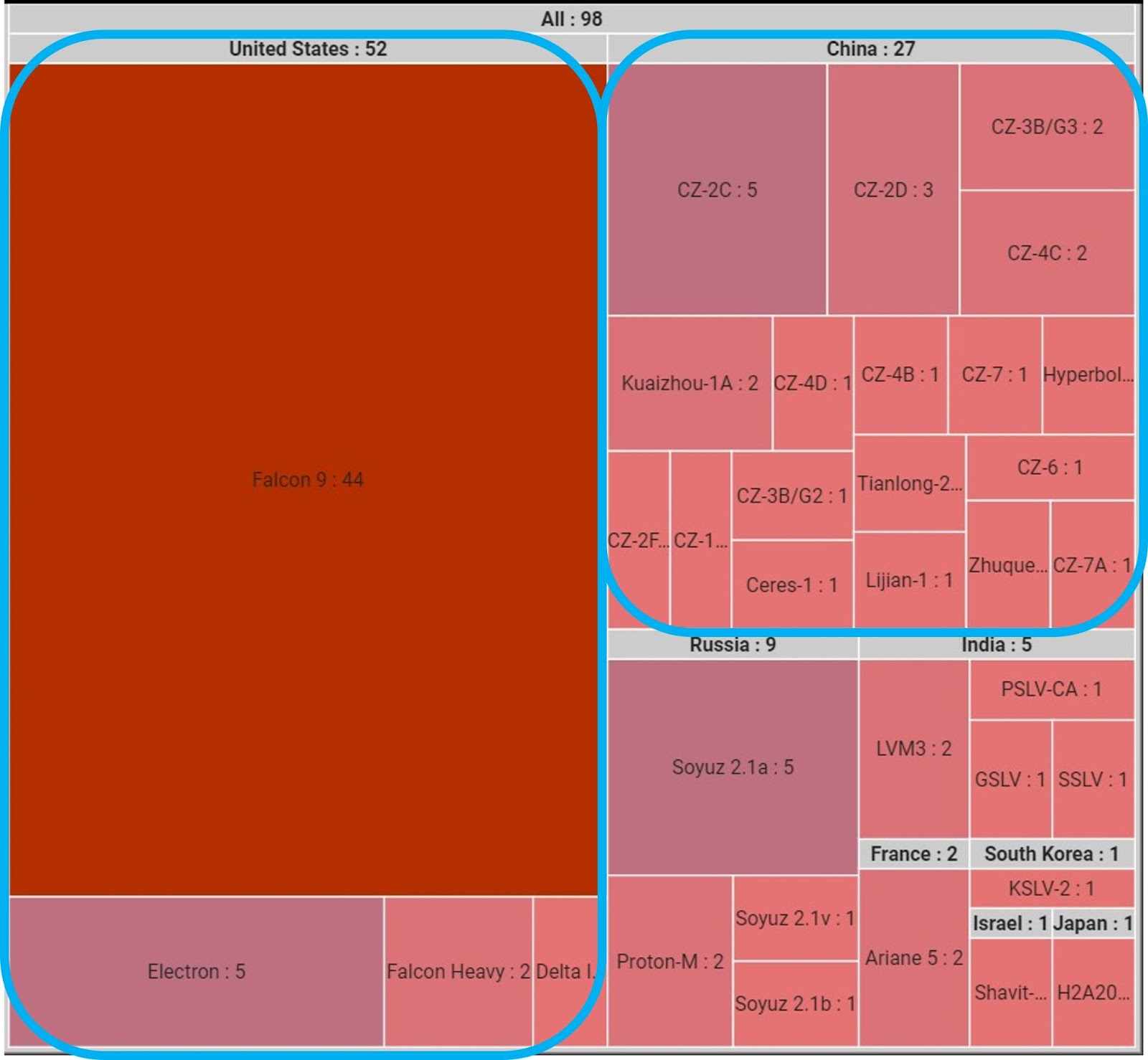

It should ask why China, for example, has so many rocket varieties. Why are the U.S. launch service providers’ offerings so spare (or non-existent)? In a half year of launches, basically three rocket types have launched from the U.S. During that same period, over 13 rocket types have launched from China (launch capacity/supply chain stability).

Orbital Launches, Jan-(mid)July 2023

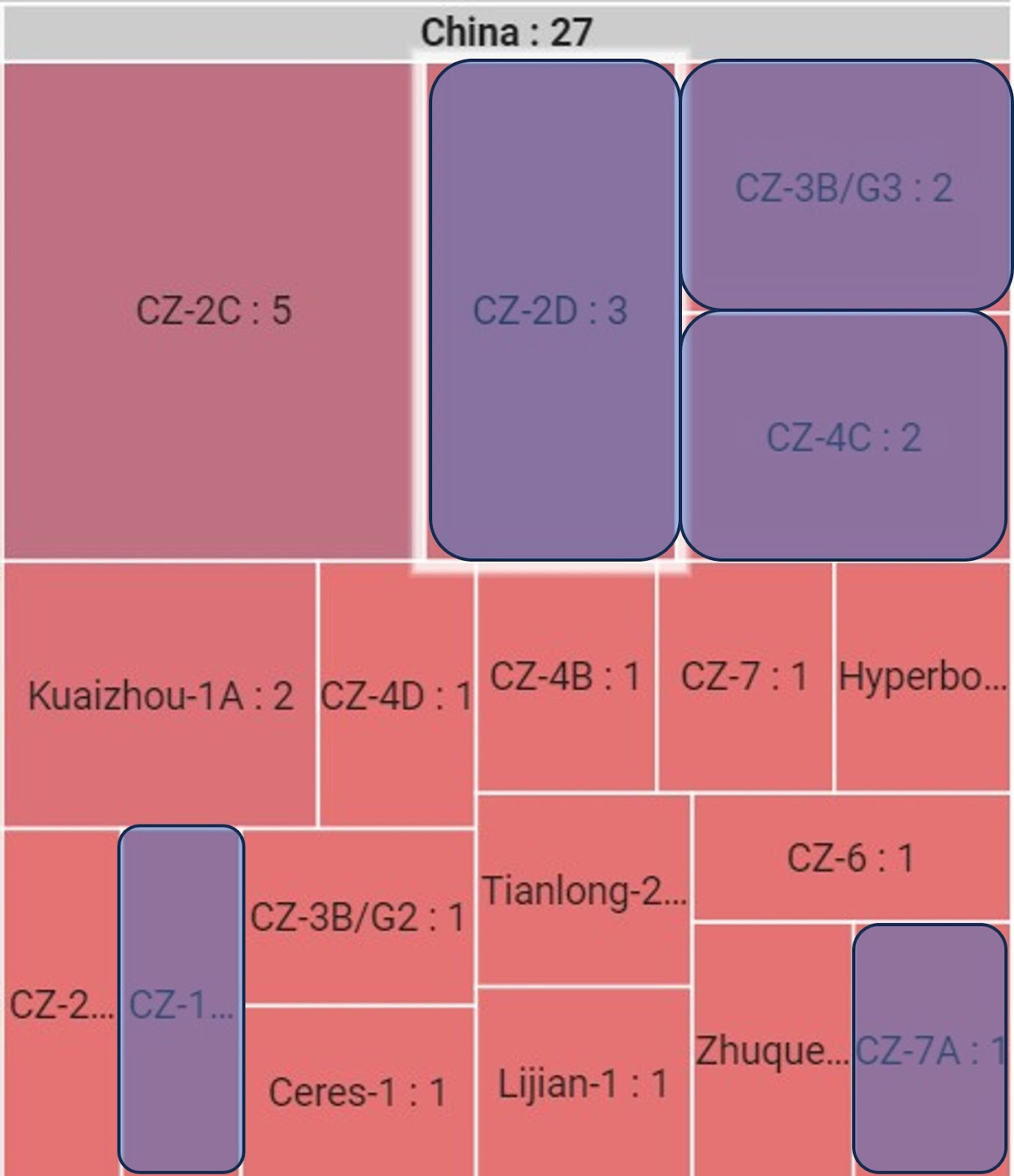

So far, China’s military has used at least five of those 13 rocket types for its launches in 2023 (below). It used one in each family, the exception being the use of both CZ-3B/G3s. The rockets used are highlighted in purple.

Jan-(mid)July 2023

China’s rockets launch from four launch complexes and launch often (resiliency through alternate launch sites/streamlined integration times). However, they do not launch as often as the Falcon 9. I’ve noted that China’s launch services launch so often because they must–many of their rockets don’t meet the lift capability of the Falcon 9. None launch as often as the Falcon 9. Still, the many launch options in China provide a stark contrast to those in the United States, a nation that prides itself on fostering marketplace competition.

Not that the U.S. and DoD should make the mistake of emulating China. As the figure above shows, China’s many rockets are the exception among nations with orbital launch capability. Instead, the difference in rockets should nudge the DoD into pursuing a different way to achieve its goals AND not become reliant on a single company for its launches. That may mean scrapping anything resembling NSSL. Adding one more competitor to Lane 2 is not even the minimum–it’s outdated and subpar thinking mixed with hope.

U.S. troops deserve much more than that.

Comments ()