Mixed Message: State of the Space Industrial Base 2022

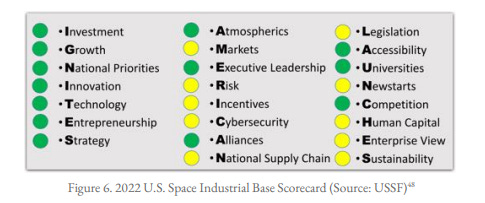

A few pages into the 136-page “State of the Space Industrial Base 2022,” I had to put it down and shake my head. My reaction was because the supposedly serious document had the following figure on page 10 of the report:

I don’t want to know how much time and brain cells were lost trying to devise ways to force or create words to spell the acronym (what the heck is “Newstarts”).

Clouding Useful Content

The report, released in August 2022, is supposed to (in its words): “...provide actionable recommendations to actors in the space ecosystem enabled by leaders across the entirety of U.S. society.” That’s a word-soupy way of saying “recommendations for strengthening the U.S. space industry.” The report reintroduces the (by now) very stale fiction of the United States competing in a “New Space Race” with China (and Russia). That idea’s prominence in the second paragraph of the report’s introduction shows how wedded the authors are to it. It’s an idea that’s so prevalent that NASA’s current administrator referenced it last month (and several times before).

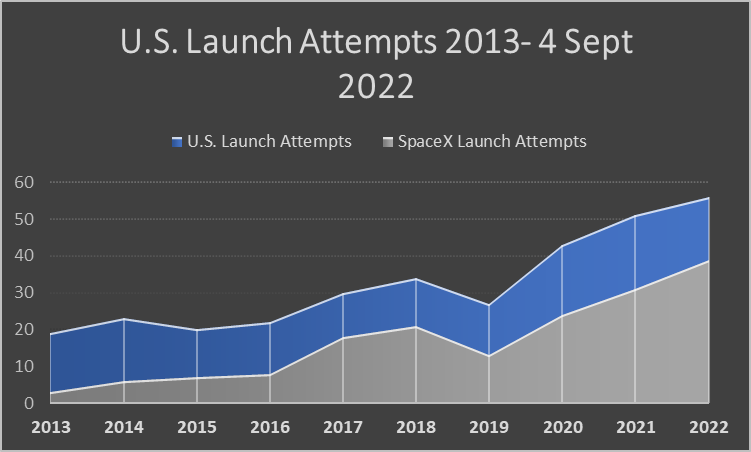

As for the forced acronym: the first acronym in figure 6 is a bit behind. Rather, U.S. launches have “ignited” since ~2017…just not in the way the U.S. military wants:

The chart above shows that one launch company is doing very well (and I’ve written of the challenges with that). The problem is only one company’s launch activity share dominates U.S. launches–a scenario the U.S. Department of Defense wanted to avoid. And yet, the U.S. military is getting much of what it wanted not long ago for space launches.

SpaceX played the game the DoD required, pushing through the National Space Security Launch certification of its Falcon 9. It created a reliable rocket. It is maintaining an operational tempo the U.S. military can’t keep up with (but wanted). It can deploy a range of satellites from the smallest to some of the largest (in Falcon Heavy form), providing payload flexibility. It’s dominating U.S. and global space launch activity along the way. Even better, it’s one more company than the DoD relied on when there was only the United Launch Alliance. Yet, despite those benefits, the DoD appears almost “anti” SpaceX, willing to risk its schedule on contracts with ULA and its yet-to-be-launched Vulcan. Is that because SpaceX, unlike ULA, is not reliant or focused on DoD missions? Is that what the silliness in the report’s figure is supposed to foster?

Considering much of the report’s other content, probably not. But it’s too bad the report begins with those acronyms and narrative reinforcements because it contains some decent observations and recommendations. While it is meant to provide recommendations for U.S. military purposes, I believe that a few of those and the observations could apply to other nations/organizations in their attempts to come to grips with changes in space technologies, processes, and economics. The report’s major observations are:

- China is determined and capable of winning the New Space Race

- New Space ecosystem at risk

- National Space Vision required

- In order to protect the Planet, we must get off the Planet

- Commercial space technology has forever changed the nature of conflict

Pushing the first bullet to the side, the other bullets could apply to the efforts and processes of most other spacefaring nations.

New Space ecosystem at risk

The risk has nothing to do with the actual vitality of the commercial U.S. space ecosystem and the companies making progress with their businesses. The authors’ elaboration of the second bullet shows that the risk to “New Space” is mainly the frozen molasses pacing that is the bureaucratic nature of U.S. procurers and policies. Instead, that slow pacing makes U.S. military space noncompetitive (in other words, the U.S. military is its own worst enemy).

Militarily then, U.S. freedoms and the troops who defend them are at risk. That risk exists because the calcification of its acquisitions agencies is so pervasive that they can’t use the newest and possibly best space technologies available. For as many excuses the DoD (and their oversight committees) throw up to the media and lawmakers for why the system is the way it is, it’s a problem in the DoD’s total control. But that isn’t the same as saying the problem is easy to solve. The DoD’s process is so slow that any U.S. competitor could use that slowness to its advantage. That sluggishness is why I think the Space Development Agency is shaking things up (which is a good thing). And yet some lawmakers would like to put a stop to the SDA’s activities.

But what about those other nations around the world? If there’s one thing that seems obvious, many of them are even more beholden to their bureaucratic security blankets and much more slow-moving (Galileo, anyone?) than the DoD. In some instances, a few encourage widespread corruption (diamond-encrusted Mercedes, anyone?). The DoD’s worry about its inability to respond quickly in acquiring valuable and new space technologies may identify a challenge other nations/organizations are dealing with (which is also, theoretically, in their control). Maybe some of them will learn from the DoD’s weaknesses. If they do not, then the vibrant, idea-laden, entrepreneurial startups in their corresponding areas might never grow.

National Space Vision required

The idea of a national space vision is not new, and the report describes its utility as most others would. Readers know I have a few opinions about these types of statements. A vision statement is such an elementary, sound idea that it’s surprising it’s not used more often to promote the U.S. government’s space plan (many businesses have a vision). It’s also a callback to how U.S. President John Kennedy’s words inspired (so I’ve heard) a generation of people to work in space. A vision statement may help even politicians understand why U.S. businesses are in space. Note that the vision should not be based on the terrible mission statement of the U.S. Space Force:

“The USSF is responsible for organizing, training, and equipping Guardians to conduct global space operations that enhance the way our joint and coalition forces fight, while also offering decision makers military options to achieve national objectives.”

Instead, the vision should be simple (again–politicians). The vision sets the goal, which is also necessary for other space organizations. The European Space Agency, for example, has the following mission:

“The European Space Agency (ESA) is Europe’s gateway to space. Its mission is to shape the development of Europe’s space capability and ensure that investment in space continues to deliver benefits to the citizens of Europe and the world.”

Probably to nobody’s surprise, it’s almost as wordy as the USSF’s statement and about as terrible. But it is, at least, agreed upon by the other member nations and therefore provides some kind of global vision critical for getting things done (not inspirational, mind you). But the results are mediocre, as ESA and a few of its members tend to focus more on the “investment in space” side, throwing money at favorite companies rather than ensuring those investments benefit people. Also, the idea of shaping space capability seems somewhat foggy. That could mean shaping inward and down rather than up and out. It’s a strange combination of words to see in a mission statement.

This is a problem companies afflict themselves with, too. They include everything but the kitchen sink, believe the words boutique, leader, disruptor, innovative, etc., are meaningful but include nothing memorable and relatable to customers and employees. I’m not a master vision writer, but I think something like the following might work, “Getting to space fustest with the mostest thanks to the brightest. Then prosper.” For goodness sake, keep it simple, challenging, and achievable. SpaceX’s statement is straightforward: “Making Humanity Multiplanetary.” Three words with impactful, inspiring promise (everyone knows that three is a magic number).

In order to protect the Planet, we must get off the Planet

This one is a little more difficult to explain, and I disagree with it for various reasons. First, it doesn’t mean quite what it sounds like it should mean. The bullet almost sounds like statements from Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk–flee the planet to survive. But that’s not the authors’ intent. Instead, they are referring to the idea of exploiting resources in space instead of on Earth, and moving, when possible, polluting activities to space (instead of pursuing technologies and techniques to keep pollution down on Earth, to begin with).

This is also a global problem. While the report’s authors are making recommendations for U.S. readers, pollution, energy generation, etc., are meaningful challenges to people worldwide. They are also interconnected, as pollution in one area of the world can impact another. Climate changes have magnified those impacts and brought on challenges for the world’s current custodians. So, hopefully, the authors’ solutions are global in scope.

They are but aren’t.

A hiccup with their observation is that it moseys into the science fiction realms of “..off-world power production, manufacturing, and Lunar resource extraction….” Of course, those technologies would be helpful. While others in China and ESA have mentioned similar wishlists, the space agency with the most budget resources and likely the highest concentration of launch experts, NASA, is having difficulty building and launching something as basic as a rocket. But the biggest challenge is that those recommendations mention technologies that aren’t mature. Worse, pursuing them may encourage governments to put off working on effective climate and pollution solutions on Earth.

Commercial space technology has forever changed the nature of conflict

Frankly, technology always “forever” changes the nature of conflict, at least until something new comes along. Chemical, tank, ICBM, drone; blitzkrieg, guerilla, nuclear triad, global reach-global power, etc.--conflict changes as technology is appropriated, which changes tactics. Changes brought about by new technologies are also something the rest of the world deals with. The report’s authors don’t mention a thoughtful solution in the section (page 82) elaborating on the observation, promoting “mandates,” forcing the DoD to use commercial products and services. Mandates are one of the sources of the DoD’s acquisition problems.

I suggest that commercial space technology is just another aspect of the constant technological changes as nations position themselves to gain whatever advantage they can from it. In this way, this bullet ties into the “New Space Risk” bullet, as, at least in the U.S., the military is very slow to adopt these changes. Similarly, not just other nations but commercial companies can learn from this concept. A company that is slow in its adoption of a technology or reaction to changing environments is refusing to acknowledge reality at its peril.

But the real problem with that last bullet is that it focuses on a trend that is going on today, which may or may not continue. It sounds profound, even though it seems obvious. Unfortunately, human nature will cause many report readers to unthinkingly latch onto that observation and turn it even more into the space flavor of the day for the self-licking ice cream cone. Embracing what the commercial sector offers to boost military capability should have always been on the table, but making it seem as if it’s the only path to the future is foolish.

Is it useful?

The report is an interesting read. But after going through its observations and the supporting information, it’s unclear how useful it is. The report’s major observations combine views of alarmism (China Space Race), pie-in-the-sky solutions, evident business practice, and looking backward. The report contains some useful ideas: satellite transponders and avoidance systems; airspace/maritime deconfliction; establishing a single licensing agency. But they are lost amidst the typical narratives, such as “more STEM,” “more money,” “more space race,” and “more government insertion in commercial endeavors.”

If anything, the report should be seen as part of a conversation for working on space industry challenges. It brings a perspective and ideas from the inevitable biases that perspective fosters. Suppose commercial space industry (and other international) stakeholders published their version of this kind of state of the industry report. In that case, it may help bring about balanced solutions to what are essentially global challenges.

Comments ()