Starship and the V2 Mindset: Tool, not Strategy

Upon reading an opinion in the National Interest, “For Space Force to Succeed, It Needs Starships from SpaceX,” several questions emerged. Of personal interest was, “How much is SpaceX paying this guy to write this stuff?” I’d like to know the rates to charge. How else to explain the author’s last paragraph:

“Only by purchasing a block of militarized Starships from SpaceX can this happen. Whether Washington wants to admit it or not, the era of space warfare is here. And Starship will play a vital role in winning that space war.”

It would be good to understand the author’s reference to space warfare. He mentioned space activities from China and Russia.

Russia’s “nuclear space option” has been a possibility since the beginning of the Space Age. But it was never a likely one. Russia has explored space weapons since before launching Yuri Gagarin into space. In a later example, it installed a cannon on one of its orbiting space stations and fired it in the 1970s. As for China beefing up its space capabilities, it is still playing catch-up with Russian and U.S. space capabilities. SpaceX, with its Falcon 9 and Starlink, had already impacted China's carefully-laid space plans before Starship's latest launch. Those, and the author’s other examples, aren’t hostilities but continued weaponization efforts.

A Plethora of Planes

I’ll be the first to admit that the U.S. Space Force (USSF) needs to do much more to get beyond its support role for the armed services. But I suspect readers may have questions like, “Why is Starship so critical to the Space Force?” How would Starship help the USSF protect U.S. interests in space? Does the author provide anything to support his call for a Starship binge?

Before answering that final question, it might be good to ask another question: does another military service, such as the U.S. Air Force (USAF), rely on one air platform to win wars? The answer is no. Just look at the aircraft from this Wikipedia table:

And that’s just a sample–more aircraft are on the table than could be reasonably presented in the snippet. Those aircraft come from multiple manufacturers: Boeing, General Dynamics, Lockheed Martin, McDonnell Douglas, Northrop Grumman, etc. Also, the paragraph above the table links to a list of ALL active U.S. military aircraft. That table shows all the aircraft the U.S. military currently uses to support and fight its wars.

The point is that while it’s nice to have a “super” aircraft ready for combat, the U.S. military wouldn't just rely on that one aircraft to win wars. It doesn’t even rely on a single service to win its wars. The USAF uses more aircraft than most nations can hope to manufacture. So, why should the USSF embrace a doctrine of dependence on SpaceX and its Starship? That’s like the USAF deciding that the only way to win wars is to fly a C-5 (and that commercial pilots will fly it).

NAZI Germany eventually developed a similar reliance on its V-2. That reliance took money and resources away from its far more effective Luftwaffe aircraft to build the more complicated but less accurate and less capable rockets (not that any of us are complaining about that).

Does the DoD NEED Starship?

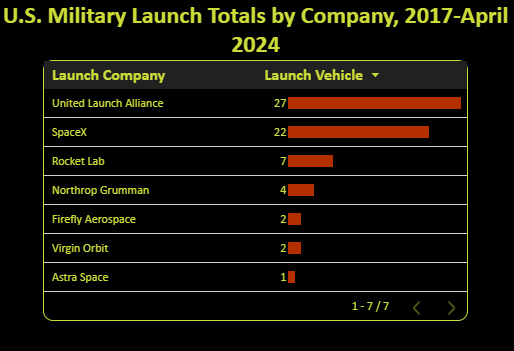

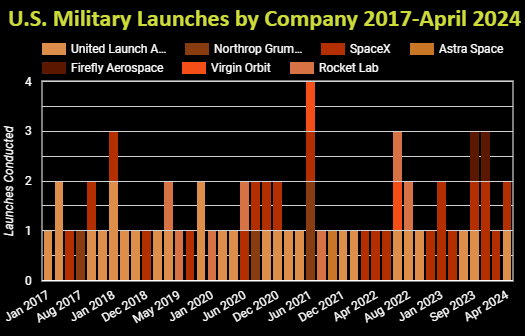

Neither the USAF nor the USSF wants a similar reliance (despite the decision to go with ULA early on). Based on the past 7-8 years, ULA’s rockets were used slightly more often than SpaceX’s for U.S. military-associated launches. The military used other launch services (listed in the chart above), but not nearly as much as it relied on ULA and SpaceX.

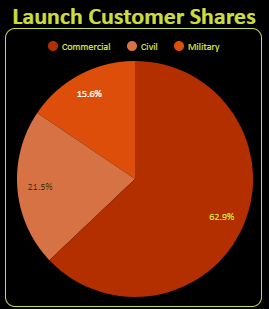

One thing to understand about those launches is that from 2017 through April 2024, U.S. military launches took about 16% (65) of all U.S. launches. That is smaller than civil (~22%) and commercial launches (63%). Based on that distribution, U.S. launch capacity could support more military launches. However, it appears the military is satisfied with its share of launches, averaging about eight annually during that time (vs. China's ~17/yr military launch average).

Based on the DoD's use of launch vehicles and its lackadaisical launch average, Starship would not result in more DoD launches or more spacecraft deployments.

It is also rare for the Department of Defense (DoD) to use any rockets to their full upmass capability. They usually don’t even come close. Based on the DoD's history and its existing programs, including those in the Space Development Agency, Starship's existence wouldn't contribute meaningfully to USSF spacecraft deployments (other than its predicted ability to deploy much more for much less). The legacy spacecraft manufacturers can't build satellites that quickly.

SpaceX and Blue Origin are developing rockets with capabilities beyond what the DoD requires today. Does that mean both fill a “vital role?” What does that even mean when the DoD is focused on “tactical” launch (which usually relies on smallsat launchers)?

However, the challenge for the DoD is that it must now rely on SpaceX for all its “big” launches. That's its vital role. The graph above shows the gradual ceding of military launch shares from ULA to SpaceX. At the same time, other companies, such as Blue Origin, haven’t fielded a rocket yet. ULA does have Vulcan, but it’s only launched once so far. While the DoD has signed contracts for ULA’s Vulcan, the Vulcan hasn’t been certified for U.S. military launches.

Again, ULA’s and Blue Origin’s lack of rockets leaves the DoD with one company for its heavy-lift missions: SpaceX. Starship will only keep the DoD dependent on SpaceX. If SpaceX draws down Falcon 9 operations as Starship's viability is proven, then the DoD will need Starship--because it might be the only game in town.

What is Starship’s “Vital Role”?

The author’s suggestion to double down on SpaceX with Starship has precedent in the example of the DoD’s acceptance of ULA’s monopoly. But does Starship’s massive potential upmass capability even come into consideration for the DoD’s plans? How does it help the USSF protect U.S. interests in space (aside from government money keeping the private sector afloat)? The author doesn’t answer that, except to note:

“In the age of contested environments, a rapidly deployable, reusable heavy-lift rocket and Starship would allow for the rapid transportation of troops and equipment—at hypersonic speeds—from one location to another.”

“Such a capability could help win future wars, where degraded environments would likely prevent the US military from employing traditional power projection methods.”

Point-to-point transportation of troops and equipment does not protect U.S. space interests. It’s just transport from one ground point to another (a la “Starship Troopers”). Even in contested environments, the U.S. military does this exceptionally well with aircraft. Without getting into debates about whether Starship, as it’s shaped today, will be able to do this, how does point-to-point terrestrial-focused transport give the USSF power projection in space?

If it becomes a reality, Starship can lift substantial payloads into orbit. That will be its “superpower.” If its stages are reusable, it can theoretically lift those large payloads inexpensively. Based on SpaceX’s successes with the Falcon 9, it would be a good idea for the USSF to prepare for Starship’s possibilities.

If the USSF wants constellations of larger, more hardened, and less-compromised satellites for all sorts of space missions for less, then Starship could help. If it wants massive crewed military space stations in Earth’s orbit, Starship could help with that, too. In time, Starship might be able to get things to the Moon. These missions fall in the USSF’s realm and could help with power projection, depending on spacecraft payloads.

But in an age when reusability is happening almost daily, it might make more sense for the USSF to buy Falcon 9s, Falcon Heavies, and Starships and train its Guardians how to operate them. This would lessen the risks of civilians being caught up in military operations. Operating rockets is good for the USSF and provides it with a bit more schedule control. It’s also suitable for the space industry–just ask the air industry and its workforce pipeline.

Going back to the USAF’s airframe inventory, it would also make sense for the USSF to buy other rockets (if it requires them) from other manufacturers (requiring them to be reusable) designed for its missions instead of designing missions around a single spaceframe. To understand that, one only has to look at the list of aircraft the other services use. However, I would be remiss not to mention that the USSF’s satellites already serve some of those roles, especially in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

To say that only Starship is crucial for the USSF’s success demonstrates a fixation on Starship, blinding him to the USSF’s needs and U.S. space interests. The author doesn’t tell us how Starship contributes to “American Space Dominance” and helps beat back attempts from aggressor space nations. The author’s examples don’t show HOW Starship can help secure U.S. space interests, only terrestrial ones. Perhaps he believes Starship’s massive size somehow implies dominance?

To be sure, the USSF faces structural and mission challenges. Addressing those challenges would go a long way toward bolstering U.S. military space activities and helping secure U.S. space interests. Certainly, Starship will be a useful tool when and if it comes along. But it should only be a part of the USSF’s launch toolset, not a strategy stand-in.

If you liked this article (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), any donations are appreciated. For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU!!

Comments ()