The Ill-Defined Space Global Orbital Launch Summary: 2025

FYI, there will be no spacecraft analysis following this Launch Summary. Also, so there’s no confusion, this is my work. It is not sponsored by anyone or organization, such as the UK government, who I work for.

Happy New Year!!

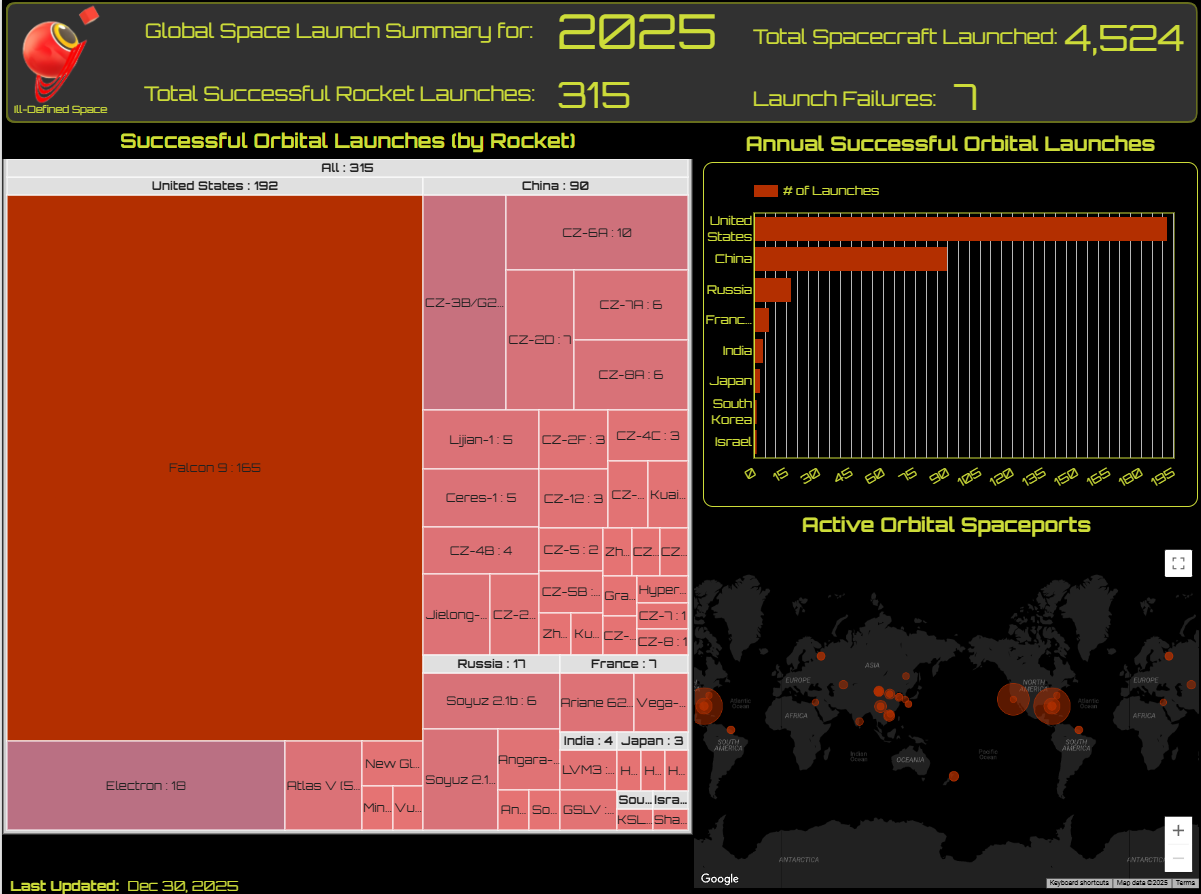

There’s no denying that 2025 was a year of record-breaking successful orbital launches: 315. It was a 24% increase from 2024’s launches (61 more than 2024’s 254–record-breaking at the time). It was also a year of record-breaking spacecraft deployments from those rockets–over 4,500–about 60% more than 2024’s 2,800+.

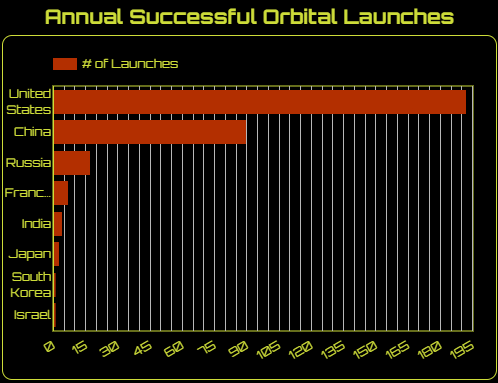

The usual nations’ rocket launch services were responsible for the majority of 2025’s launches: those of the U.S. and China. Together, successful orbital launches from those nations accounted for ~90% of the world’s launches.

Separately, 192 U.S. launches made up ~61% of the 315 worldwide, up from 154 in 2024. Ninety launches from China took ~29% (not even half of the U.S. launches in 2025), up from 66. Successful launches from other nations’ launch operators (Russia (17), India (4), France (7), Japan (3), Israel (1), and South Korea (1)), while important to those nations, did not account for significant shares of 2025’s successful launches. Less launches also indicate they lofted less mass and spacecraft into space (shorthand: less space capability).

I will only focus on Russia, China, and the U.S. for the remainder of this orbital rocket launch analysis.

Not Dead Yet–Russia

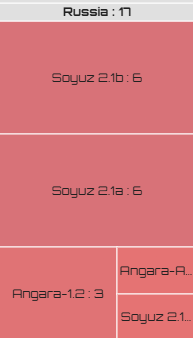

In Russia’s particular case, despite stories abounding about that nation’s rogue, wandering “inspektor” satellites (which is a problem), the country’s low launch total (17) indicates it deployed very few of those and other spacecraft in 2025. Its launch cadence in 2025 was a little over once every month, equaling its 2024 launches. It was also slightly ahead of its 2018 launch totals, showing not much dynamism and little growth in its launch activities during the past eight years.

Strangely, it appears that the war has not necessarily impacted its orbital launch rates, since they equal pre-war numbers (at least eight years ago). However, before 2016, it was not uncommon for Russian launches to reach over 30 launches annually.

The fact that three-quarters of Russia’s launches in 2025 used the reliable and upgraded (if aging) Soyuz launch system indicates an inability for the nation to field more modern, more capable systems. While Russia’s Angara 1.2 is newer (three launched in 2025), the rocket cannot lift close to the mass that the Soyuz rocket variants can. An Angara-A5 also launched in 2025–once–which IS more capable than Soyuz. But the system is older, and the Russians are very slow in fielding it, launching it successfully four times, including its debut launch in 2014.

Perhaps Russia’s current reliance on the Soyuz is a choice, one in which its government is choosing to invest in other technologies/priorities instead of its space systems?

China’s Continued Rise (Mostly due to Internal Customers)

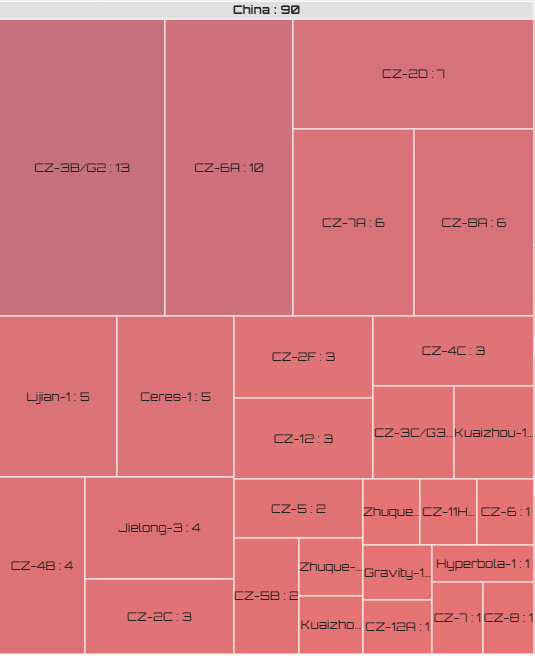

On the other hand, China’s rocket launch services show evidence of plenty of investment whether subsidized, direct, or commercial. The primary evidence is based on the record number of launches they’ve conducted in 2025: 90. That’s ~24% more than the 66 they launched from China in 2024 and not quite triple the number of launches they conducted in 2018 (the earliest year I’ve collected about them). Their overall 2025 launch cadence was slightly more than once every four days. More launches mean the nation deployed more mass and spacecraft, enhancing its space capability significantly, in 2025.

About 20 (~22% of 90) launches from China were for constellations such as Qianfan, Guowang, and Adaspace. Three more launches were conducted for deploying Geespace’s GeeSats, a constellation of commercial satellites with navigation, communications, and remote sensing capabilities. At least five of the country’s rocket launch services appear to be commercial. With some exceptions, most launches from China were for China-based customers.

The fact that, despite its parochial focus, China’s space launches place it second globally should be a wake up call to outside competitors. The activities and apparent success of China’s orbital launch operators so far, primarily driven by customers in-nation, might prove attractive to customers in other nations. Especially if costs and availability concerns outweigh political and intellectual property risks, should the nation choose to become more aggressive in the global space markets.

Not only have China’s rocket launch operators increased their launches, but they also used a diverse range of rockets, some much newer than the Falcon 9. Please take a look at the treemap of China’s rockets and their variants below.

That’s 27 rockets the country can draw from to launch spacecraft, indicating investment in not only rocket development, but the launch infrastructure, including the ability to launch from ships/barges. Some of China’s companies are pursuing first-stage reusability. The rocket diversity from China versus the dearth of such from European nations should be reason enough for Europeans to consider changing their space acquisitions processes.

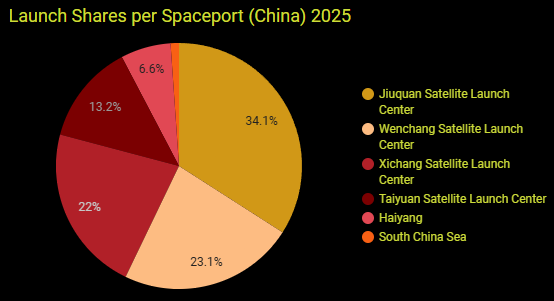

China has four primary spaceports supporting the diverse launch systems located in Jiuquan, Xichang, Taiyuan, and Wenchang. Jiuquan hosted the most launches in 2025 (31), while Taiyuan the least (12).

Of China’s rocket inventory, it appears that two–the CZ-5 and Zhuque 3–can nearly equal or exceed the Falcon 9’s upmass capability. Not one of China’s 27 rocket types launched in 2025 has achieved reusability capability (yet).

U.S. Launches: Unbridled but Dependent

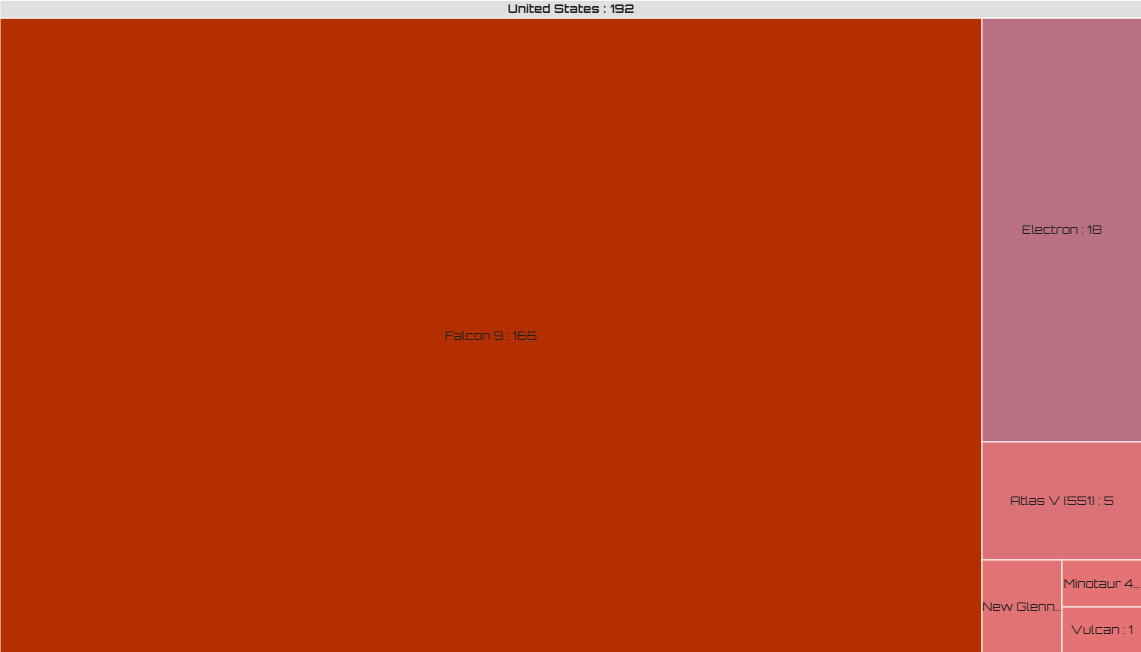

U.S. rocket launch services conducted the most successful orbital launches in 2025: 192 (~25% increase from 2024’s total of 154). It was also a record number for launches conducted by U.S. companies in a year. And, the U.S. is the only nation with not just one, but two, companies launching reusable orbital rockets. Five U.S. commercial companies contributed to the 192 launches, in order of contribution (highest to lowest): SpaceX, Rocket Lab, United Launch Alliance (ULA), Blue Origin, and Northrop Grumman.

That total means that U.S. launches averaged less than once every two days in 2025. It also points to U.S. rocket launch companies with a ~61% share of the world’s 315 successful orbital launches.

Of the 192 launches, SpaceX conducted 165–nearly 86% of all U.S. launches in 2025 (up from the previous year’s 134)--all using the Falcon 9. Rocket Lab launched 18, more than the 14 launches it conducted in 2024 (~9% of U.S. launches). ULA’s six launches (one more than its five in 2024) accounted for a little over 3% of total U.S. launches in 2025. Blue Origin launched its New Glenn rocket twice (1% of 2025’s U.S. launches), with 2025 being the inaugural year for the company launching rockets to orbit. Northrop Grumman launched once–a Minotaur 4–not even gaining a 1% share of U.S. launches in 2025.

Most of SpaceX’s launches (~74%) in 2025 deployed its Starlink network of satellites: 122 of 165. That indicates that slightly over a quarter of its 2025 launches, 43, were for spacecraft OTHER than Starlink. In 2024, SpaceX launches for other than Starlink totaled 44. While two years don’t make a trend, the total non-Starlink launches each year might demonstrate a bigger launch market, which works against one justification (not enough customers to increase launches) that competitors provided not to pursue reusability. It may also be that relatively inexpensive Falcon 9 launches are generally more attractive to a wider group of customers than in the past.

That SpaceX experienced no Falcon 9 failures is pleasantly surprising, considering its increased launch cadence in 2025. Whatever assurance programs the company has in place appears to be working. That the company is more familiar with its Falcon 9 after use than any other company on the planet probably contributes to the Falcon 9’s reliability.

However, another notable achievement–Blue Origin’s landing of New Glenn after an orbital launch–will likely provide similar benefits to the new rocket’s reliability over time. Blue Origin just needs to find more customers so it can launch (and land) New Glenn more often than its current two-per-year. The rocket’s upmass capability outclasses the Falcon 9, which means it could launch more mass less expensively than SpaceX…eventually and if motivated.

A second launch system with first-stage reusability bodes ill for companies still pursuing the development of totally disposable rockets. More powerful, reusable rockets are capable of deploying satellites in higher orbital inclinations, even sun-synchronous orbits. Those high inclinations have been used as reasons to build spaceports in higher latitudes, such as Scotland or New Zealand. SpaceX has demonstrated the business case for launching SSO missions from Florida with Falcon 9 and a few of its Transporter rideshare missions. And it’s doing it for far less than services using existing smallsat rockets.

The existence of multiple reusable rocket systems in inventory may make the need for more varieties of smaller rockets (as in China) and smallsat-dedicated rockets in particular, less advantageous. Especially when spaceport infrastructure must be updated to handle a variety of rockets. As important, the existence of a reusable New Glenn means that the United States might eventually not be as reliant as it currently is on SpaceX.

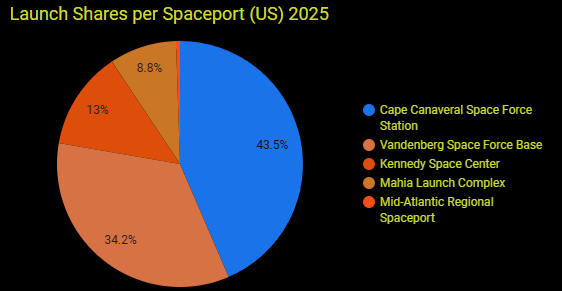

Five spaceports were used to launch U.S. orbital rockets in 2025: Mahia Launch Complex (New Zealand), Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (Florida), Vandenberg Space Force Base (California), Kennedy Space Center (Florida), and the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (Virginia).

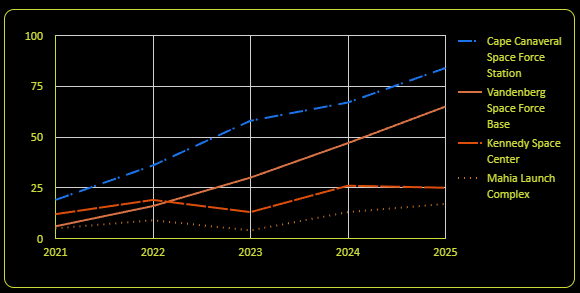

Of all regions and nations, Florida’s two spaceports were the busiest in 2025, with the greatest share of U.S. launches: 109 (~57% of U.S. launches and ~35% of the world’s). It was not just the U.S.’s, but the world’s gateway to space. If Florida were a sovereign country, it would have been the foremost launch nation in 2025, outpacing China’s launch services. The state has also seen a significant and extremely rapid increase over the past five years (~252%) from the 31 launches conducted by Florida’s two spaceports in 2021.

Whatever spaceport infrastructure improvements that are being implemented for CCSFS and KSC can’t happen soon enough if 2026’s launches equal or exceed 2025. This includes possible opportunities for growth in the communities and businesses around CCSFS and KSC, especially for satellite manufacturing and spacecraft processing. These scenarios are possible should Blue Origin and ULA increase their launches alongside those from SpaceX. Florida is also the only region that hosted two companies launching reusable (1st stage) rockets in 2025.

Launches from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California have gone through more drastic increases during the same time, from six in 2021 to 65 in 2025 (an ~983% increase). Sixty-four of those were Falcon 9 launches. The same challenges and opportunities likely apply to Vandenberg as KSC and CCSFS.

Mahia Launch Complex in New Zealand saw modest growth in orbital launches from 2024’s 13 to 17 in 2025, all of it dependent on Rocket Lab’s Electron. While there might be more growth in the wings, it’s doubtful that the growth will be similar to that experienced by Florida’s and California’s spaceports. One reason–Rocket Lab’s newest planned rocket, Neutron, will not be launched from Mahia. Another is there are no other tenants for New Zealand’s spaceport aside from U.S.-based Rocket Lab. A third may be less need for smallsat launchers like Electron with SpaceX and others’ satellite rideshare programs.

Overall, increased launches globally during 2025 imply an increased demand for launch services and rockets, which in-turn means more satellites were launched to provide expanded or new services to customers on Earth. ~70% of 4,500+ spacecraft deployed in 2025 were Starlink satellites. However, that still means nearly 1,300 spacecraft were for other missions and customers in 2025, up from 800+ in 2024. While SpaceX will continue launching more Starlinks in 2026, it’s unclear if the growth from other deployed spacecraft will continue.

But it is possible based on the past few years as well as the new launch systems coming online.

Where’d all the nifty charts in this analysis come from? Well, except for the spaceport information, the rest are free at: https://www.illdefined.space/globalspace/. You might have to scroll down and select 2025 under the “Space Activities of Previous Years” section. Since I’m working, these might be slow to get updated–but they will be eventually. It’s not just one dashboard, but three. Just use the drop-downs/arrows at the bottom of the dashboard frame.

Comments ()