The Potential Horror and Devastation of Progress

One update that just popped up yesterday: the EULEO constellation has friends in high places, as the EC’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board rejected the constellation’s assessment twice, but like Athlete’s foot, the program still lives. The reasons for rejecting EULEO is best left to SpaceNews’ writings, but in short:

- “a lack of “analytical coherence” about why the proposed constellation is the best solution to the problems it is intended to address about broadband access and secure communications”

- “use of a “predetermined technical solution” that isn’t specified and a lack of a timetable.”

- “concerns about the validity of the data the commission used to back the proposed constellation”

But those rejections have been overridden because of the constellation’s “political importance.” Also, Thierry Breton keeps using Galileo as his best example for implementing EULEO, when he really shouldn’t:

“As far as this new constellation is concerned, this is our Galileo moment, in you like, in terms of connectivity.”

More like “Galileo decades.” Sigh!

On to our regularly scheduled programming.

It’s ANOTHER Starship article! I suppose it was inevitable since Elon Musk presented his Starship update last week. Generally, the update upshot is there were no significant new developments to the program and that Starship will be ready when the FAA wraps up the bureaucratic exercise known as an environmental assessment–by March. That was the plan until the Federal Aviation Administration pulled a “Lucy” again and “snatched the football” away from SpaceX, moving the projected assessment finish date to March 28.

There were quite a few “what if” questions concerning possible consequences from an opaque (and apparently flexible) process schedule conducted by an organization of public servants. Musk could only shrug his shoulders and carefully answer those questions as well as he could. Why the FAA chose to conduct the assessment so late when Musk made it pretty clear his company would do this eight years ago should be asked. It’s a question that should be something a congresscritter or two should ask the FAA and make the managers in the organization very uncomfortable. Another question would be: why is an established process the FAA uses routinely changing dates for the second time? And how often does that happen? And, yes, it would be great if all FAA employees involved wore Lucy’s blue dress.

But the FAA isn’t the only government agency playing catch up with SpaceX’s Starship development pacing. It appears that some NASA folks have finally begun paying attention to Musk’s ambitious project. That little bit of information comes courtesy of Politico’s “Why Musk’s biggest space gamble is freaking out his competitors.” According to Politico, those SpaceX plans are disrupting the sphincters of those folks as they come to terms with what a working Starship may mean to NASA and other industry stakeholders.

The following only focuses on rocket launch industry impacts.

People Get Ready, the Starship’s Comin’

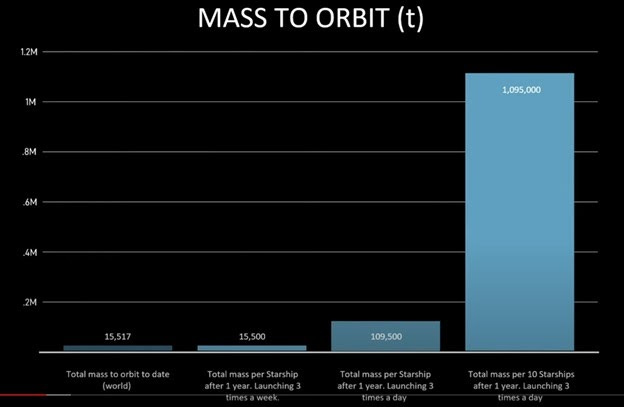

Over the years, I, and others, have provided a few guesses of what Starship will do to the industry. With the qualifier that Starship must be operational, the consensus is that it will cause a global rocket company culling. Then there’s the fact, verified in Politico this time, that it’s very apparent NASA and the other agencies aren’t remotely ready to face the sea change Starship will bring. Just look at the mass capability chart Musk presented during the update.

It should be emphasized that the chart above is relatively modest if Starship becomes operational. Musk made it very clear that the goal is to launch more than three times per day and have more than 10 Starships on tap. Nothing currently on any government mission docket will take full advantage of Starship’s 100-150 ton capability, which means the U.S. government is already behind. And even though using a Starship will cost, AT MOST, $10 million per launch ($50/kg–Musk’s words during the update), I’m confident that SpaceX will still be forced to “compete” against other companies during overly long U.S. government launch contract selections.

Starship’s mass capability may not have any initial relevance because there don’t appear to be any companies or agencies ready to take advantage of it. But the cost to use Starship will be so low that even launching undersized spacecraft to orbit will still make sense and appeal to many customers. Imagine paying $500-$600 to SpaceX to deploy a single 6U cubesat. Or, more likely (and more useful), paying $5,000-$6,000 to deploy a 100 to 120 kg satellite. That’s about one-third the current price to deploy a 3U cubesat using SpaceX’s Smallsat Rideshare program on the Falcon 9. Such low pricing would allow a company like Planet could deploy three 12U cubesats for less than it currently costs to launch a single Dove.

It’s not even a question of whether the market for SpaceX’s Starship service exists. The projected prices to launch spacecraft with it are unprecedented, but (and this is guessing) they seem so low that nearly anyone interested in deploying a satellite can do so with Starship. Although, I suggest that SpaceX consider sponsoring programs that educate and encourage people about the possibilities of how a satellite or satellite constellation can help them reach their project goals. Musk is offering an inexpensive launch capability with Starship, but it will also be rapid to launch again after it returns. He talks about Starship turnaround times in hours, not days or weeks.

That quick turnaround is beyond (and better than) the capability the Department of Defense has dearly wanted in the form of Operationally Responsive Space (now Tactically Responsive Launch) for decades. And yet, the Space Force and others will still select ULA’s Vulcan, even though it will cost nearly 10X as much per launch. The SF will continue trying to court small rockets (I guess because small is supposed to equal fast?) from startups with nothing but dreams and gumption for responsive launch. Why do I think that? Because the SF is doing it now, taxpayer stewardship be damned. But that will only last so long.

The mission is the priority for the SF, and that priority will eventually supersede any loyalty to ULA and others. Imagine what a military space force could do if it can suddenly deploy capable AND robust satellites–basically in-space versions of tanks that will scoff at the prospect of hitting micrometeoroids and regular orbital debris. They will be designed to absorb or deflect kinetic and energy weapons aimed at them. Or maybe they’ll be more maneuverable because more mass in the form of propellant can be lifted. ULA and Northrop Grumman don’t have that capability, so the military will eventually, grudgingly, turn to Starship because the mission to impose the U.S. will on an opponent is presumably enhanced through the capabilities SpaceX’s offering allows it to field--at least until a viable competitor comes along.

U.S. agencies and companies aren’t the only ones unprepared.

Starship’s Global Impacts

France’s Arianespace looks downright backward when comparing its latest developed rocket with Starship. Its strategy seems based in a world with no SpaceX, with the company set on using the Ariane 6 (which will conduct its first launch a quarter or so after Starship’s first attempt). The focus doesn’t seem to leave room for concern about industry possibilities and consequences when Starship begins launching satellites. However, the strategy does seem to hinge on ESA and the EU supplying enough satellites to justify the Ariane 6’s development.

Historically, Arianespace’s bread and butter were commercial communications satellites. But if high mass satellites can be launched for low cost, do satellite operators embrace that change? Does deploying significantly larger (30 tons, at a guess) communications satellites give those operators an advantage? Were there compromises being made on power, antenna size, and transmission rates that would be eliminated or minimized through the use of more mass? Suppose those factors come into play because of Starship’s projected capability. In that case, Arianespace will not get those customers, not even if they’re European, because only one rocket will be able to lift that much mass. But, Arianespace will survive because of government intervention, with no commercial customers stepping up to use more expensive but less capable launch capability.

China isn’t ready. It’s been confidently following its path to space. We would know, though, if China were ready because we’d suddenly be seeing pictures of huge stainless steel rocket prototypes (hard to hide from overhead imagery). China’s industry still likes to copy successful technology, but curiously haven't been able to crack reusability seven years after SpaceX's initial success. Also, China’s market is isolated and currently not impacted by SpaceX’s Falcon 9, which implies Starship won’t impact China’s launch activity. It will, however, impact foreign customers that might have considered going with China’s services. Once we see objects similar to multiple grain silos and water towers in the middle of the Gobi Desert, we’ll know that China is finally taking Starship seriously.

As for operational rocket launch companies in other nations, I guess Starship’s impact will be benign on systems with high government subsidization. I suspect Japan will continue its HIII efforts, if only for pride’s sake. That nation has had the usual program difficulties getting its latest rocket online, but the HIII will probably serve Japanese scientific and military missions, and not much else (based on what the HIIA has launched).

I’ve observed that India’s space program wasn’t necessarily designed to compete with U.S. and European companies. India has its plan and doesn’t seem worried about how many rockets it launches. The country appears to be focused on having enough rockets to get its various missions done (although there are some commercial efforts underway there). And Russia will continue using its Soyuz rocket for International Space Station activities while supporting Arianespace with its OneWeb launches. Russian space industry and power is not what it once was, however, and every announcement of a "new" rocket system should be taken with a boulder of salt. But no other rocket companies from those nations are even close to the point of launching satellites into LEO for $50 per kilogram.

The result: the companies currently competing with SpaceX–ULA and Arianespace–will likely become commercially irrelevant (ULA is pretty close to that point already) within a few years of Starship’s operational introduction. They have nothing publicly planned that would compete with Starship. ULA’s increasing weakness means that the U.S. military and NASA will become more reliant on SpaceX than before, with no real competitors (maybe New Glenn? But it needs to launch). China will keep marching down its path and start developing prototypes, which means it will have Starship-like capability. However, it will be behind SpaceX’s efforts.

Hope isn’t Strategy

The point of describing one of the more likely outcomes of Starship’s impact is this–hoping that SpaceX won’t successfully develop Starship will probably work out about as well as hoping that it couldn’t develop the Falcon 9, reusability, and Starlink.

Sure, there were (and are) valid reasons to doubt success in any one of those endeavors, as there are with Starship (there are always reasons why something won’t work). But wouldn’t a business and its stockholders be better served with business plans that include Starship’s success–just based on SpaceX’s record? Not anticipating success for SpaceX’s other projects doesn’t seem to have worked out so well. To reiterate, we’ve seen what happens to companies who hope SpaceX goes away, and it isn’t pretty. So why not anticipate success, however small it may seem?

To be very clear–anticipating success is not the same as guaranteeing it. Starship is currently a static display on a pad in Texas–until the FAA decides it’s done enough navel-gazing. Focusing on why Starship will change the industry:

- Rapid turnaround of the rocket (hours)

- Inexpensive mass transportation costs ($50/kg)

- Large mass capability (100-150 tons)

A strategy, then, should include manufacturing launch capability that will at least do those things. Subsidized rocket launch companies may go that route. But for competitive commercial companies, whatever strategy is chosen should be quicker to launch, return, and launch again, reliably. It should anticipate transporting mass for much less. And, if possible, it should require the ability to lift more. And, it probably shouldn’t meet SpaceX’s strengths head-on.

That’s just what’s needed to become a peer to a capability that potentially comes to fruition two months from now. To beat SpaceX will require more than equaling that status quo. Whoever is interested in competing in this market must determine if any of those are even feasible strategy goals. That would be more than what SpaceX’s current competitors appeared to have not done–which is a shame.

Comments ()