Maps, Streaming Video, and Earth Observation

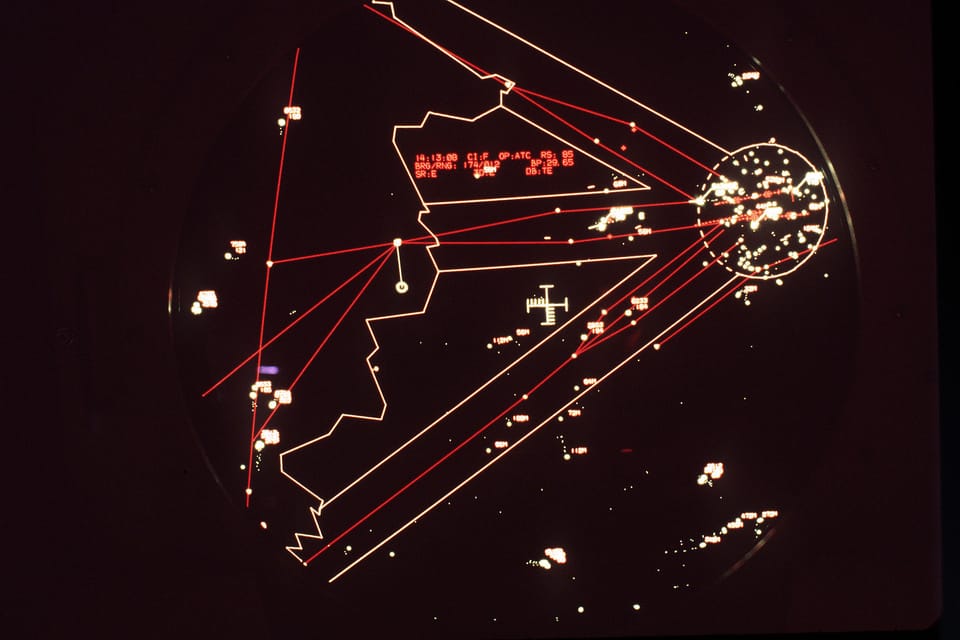

A long time ago, I managed to acquire what I thought was an interesting map. It was rather large--about the size of a 4X8 wall panel--and when laid out, it had a map of East and West Germany on it. Of particular interest to me was a layer of information superimposed on the East German side--the air corridors connecting West Germany to West Berlin. For those who never lived during that time, those air corridors (there were three) were the only way aircraft from “The West” could fly into West Berlin, safely. If an aircraft strayed from them, they put passengers and crew at risk of being shot down by Soviet and East German militaries.

That, at least, was the theory until Mathias Rust proved there were some holes in it.

The reason why I bring up the map of Germany is because how I used it (or didn’t use it) may be representative of how a lot of people use maps now--including their use of overhead imagery provided by Earth observation satellites. While that map was interesting, I kept it more as a historical curiosity than as an actual, useful tool. I never used it, except for occasionally unfolding it, looking at it for a little bit, then putting it away.

Tools or Entertainment?

For me, maps and overhead imagery are tools. And while there appears to be more access to both, on my laptop or especially using a smartphone, it’s normally still the case that the only time either gets pulled up on the screen is when I’m concerned about traffic. That’s my use-case. Which is why this LinkedIn article, “Netflix and Earth Observation: Pondering the Strange Similarities,” caught my attention. In my world, Netflix is entertainment. Earth Observation is a tool.

To be fair, the article’s author, Aravind Ravichandran, admits his article is more of a rambling than a professional write-up. But I often find ramblings very interesting, because the thoughts within are typically less inhibited, less fearful than sponsored formal pieces. Aravind’s willingness to play around with his thoughts surrounding the Earth observation (EO) space industry provides a useful jumping-off point for further discussion.

In the article, the author points out the similarity of a particular challenge--content searching--between streaming sources and EO companies. Both, he notes, have made the search for their offerings more complicated:

“Here is where I go back to my video streaming analogy. Similar to the options there, each of these providers below have their own differentiating content. Netflix offers ‘Lost in Space’, Amazon offers ‘The Expanse’, Disney offers ‘Star Wars’ while HBO offers ‘Game of Thrones.’ Similarly, Maxar offers 30 cm resolution, Planet offers daily frequency, Iceye offers radar data while Copernicus is free. As with the former case, each of the satellite data providers have great content i.e. data. Each of them offer different types and configurations of data which are all essential components for solving various industrial, policy-based and environmental use cases.”

This is true. Each commercial EO company offers different products in different ways, similar to how streaming services offer different content. But, unlike the streaming services, the EO companies’ product offerings aren’t user-friendly. At least, not friendly to users who aren’t familiar with geospatial-intelligence products. Even with the plethora of streaming services that vie for a user’s attention and require some decision-making, once a user has selected a service, getting to the content is very simple (even for someone not familiar with a particular service).

The same can’t be said for Earth observation products. At the end of the article, the author mentions a few suggested approaches for increasing awareness of EO products: aggregators/marketplaces, insight-as-a-service, and consultancies/advisory firms. I am not sure those suggestions truly make it simpler for less sophisticated customers to use products. In fact, I think each EO company, or EO analytics company (like Descartes Labs), have tried some of these approaches already.

Other analogies in the article have to do with how users aren’t aware of EO data products, unlike extreme awareness of streaming service offerings. The author also posited that the reason EO companies’ products are not on users’ radars might be because those companies are at a development stage equivalent to internet web browsers in the early 2000s.

Interesting thoughts, but some other characteristics and some history should be brought to the fore to emphasize why EO is not on the public’s mind as often as Netflix, Hulu, YouTube, etc. I would observe that EO is not close to an early 2000s browser development stage. Some of it is to do with the initial focus of video streaming companies, but a lot more is likely to do with historical focus and current regulation surrounding EO.

Looking at the market of the streaming companies, each one started out to provide commercial services to customers. From the get-go, then, these services were attempting to gain more customers, each one trying different ways to gain them. Hulu’s offerings were free with commercials, while Netflix transitioned from DVD mail rentals to video streaming for a monthly fee, and YouTube allowed cat videos to be freely disseminated onto the internet.

Obviously, things have changed with each one of these streaming services. Competition has come out of the woodwork in many forms in the streaming entertainment options including dedicated video game channels, DIY options, and more. But always, these options were set forth in the public to use and maybe to buy. Unlike EO company products.

A Few Reasons Why EO isn’t as Popular as Video Streaming

Earth observation from space in the United States has been around longer than video streaming. When the first CORONA satellite took pictures of the Soviet Union below it, the year was 1960. This means nearly 60 years of EO experience (longer than the world’s experience with the internet) have elapsed since those first reconnaissance images...but people aren’t aware of EO products today? How does that happen?

One explanation might be that most of the data from those satellites was classified. The satellites themselves were and are classified.

EO imagery like that gathered with CORONA starts with the military--and intelligence specifically. For a very, very long time the public might have been aware of U.S. “spy” satellites orbiting the Earth, but the products, whether resulting from optical, radar, infrared, laser, or radio-frequency collection means, were (and are) all classified. The public never got the opportunity to be familiar with those products because of national security reasons. Even today, the U.S. military and civil agencies seem to get very antsy when any kind of EO product (remember the SpaceX/NOAA kerfuffle nearly two years ago?) appears close to violating their rules.

Which may be a second explanation for the public's lack of awareness: EO regulation based on national security concerns.

The product focus for at least 50 years of EO collections was military--with some civil (weather, environment) added to the mix. Those decades of classified U.S. military EO collection operations impact current U.S. government attitudes toward EO, inherently building up a “chilling effect” when it comes to commercial EO companies and their data.

Imagine Netflix, going back to the analogy, having to worry about whether its streaming is “too good.” If a Netflix video was too high-definition, it might run the risk of being investigated and shut down, because it demonstrates just how sophisticated streaming technology is today to potential competitors. That scenario sounds ridiculous (rightfully), which is why there are actually so many different ways to stream videos on the internet.

But U.S. EO companies do have to worry about these kinds of rules. If a product looks like it might become “too good” then it’s a national security problem--and there’s only one kind of customer for that product. In some ways, the new commercial EO companies such as Planet face a very distinct disadvantage because if any one of them came close to producing anything better than 30-centimeter resolution imagery, they probably then have a product that, while useful to the public, will probably never be seen by it. That kind of prospect likely has a chilling effect on all those companies--unless their focus is selling to the U.S. military only.

Groundhog Day

U.S. commercial companies (in this case EO companies) are hobbled by government regulations and history. EO companies like Planet, Spire, and BlackSky all offer products that were only meant for government servants not too long ago. Because particular people to this day are still worried about controlling that information, rules remain in effect that keeps those EO companies off-balance--and at a competitive disadvantage globally.

To bring it back around, competition, whether in the military or commercial arena, only serves to hone products and services. We saw what happened (in a very short time) in the commercial video streaming market when there is competition--the technology improves. The software becomes more capable and easier to use. And when there was nothing more to do with those, then the entertainment gets better (or more diverse). In some cases, it got cheaper. Each company attempting to gain an edge on its competitors. Was there any kind of government regulation for these companies to worry about?

Maybe the same sort of mindset, and lack of regulation, needs to happen with commercial EO companies and their products, make them better, more user-friendly, to gain the public's mindshare? Until that happens, those companies may find themselves courting government customers again and again.

Comments ()