Thinking About: SpaceX’s Latest Rideshare Deployments & Starlink Lasers

SpaceX--specifically Elon Musk--has a way of making people pay attention. The company just launched a rocket on 24 January with a record number of satellites on board--143. SpaceX noted that this was the first launch dedicated to rideshare, meaning customer satellites outnumbered its Starlink satellites on the same rocket. And we see this is true--only 10 of the satellites were Starlink satellites, increasing the total number of Starlink satellites deployed to 1,025.

Those Starlinks are the first SpaceX satellites to be deployed into polar orbit. More interestingly, they all have laser terminals, which SpaceX will test (and quickly employ) as optical inter-satellite links (OISLs). Including the two test prototypes the company deployed late in 2020, the total Starlinks with OISLs is merely 12. Musk clarified on Twitter that for 2021, only the Starlink satellites headed for polar orbit would have OISLs. Beginning in 2022, all Starlinks deployed will have OISLs.

Both rideshare deployments and Starlink OISLs are significant. Starting with the rideshare stack.

Ready for Rideshare Long-haul

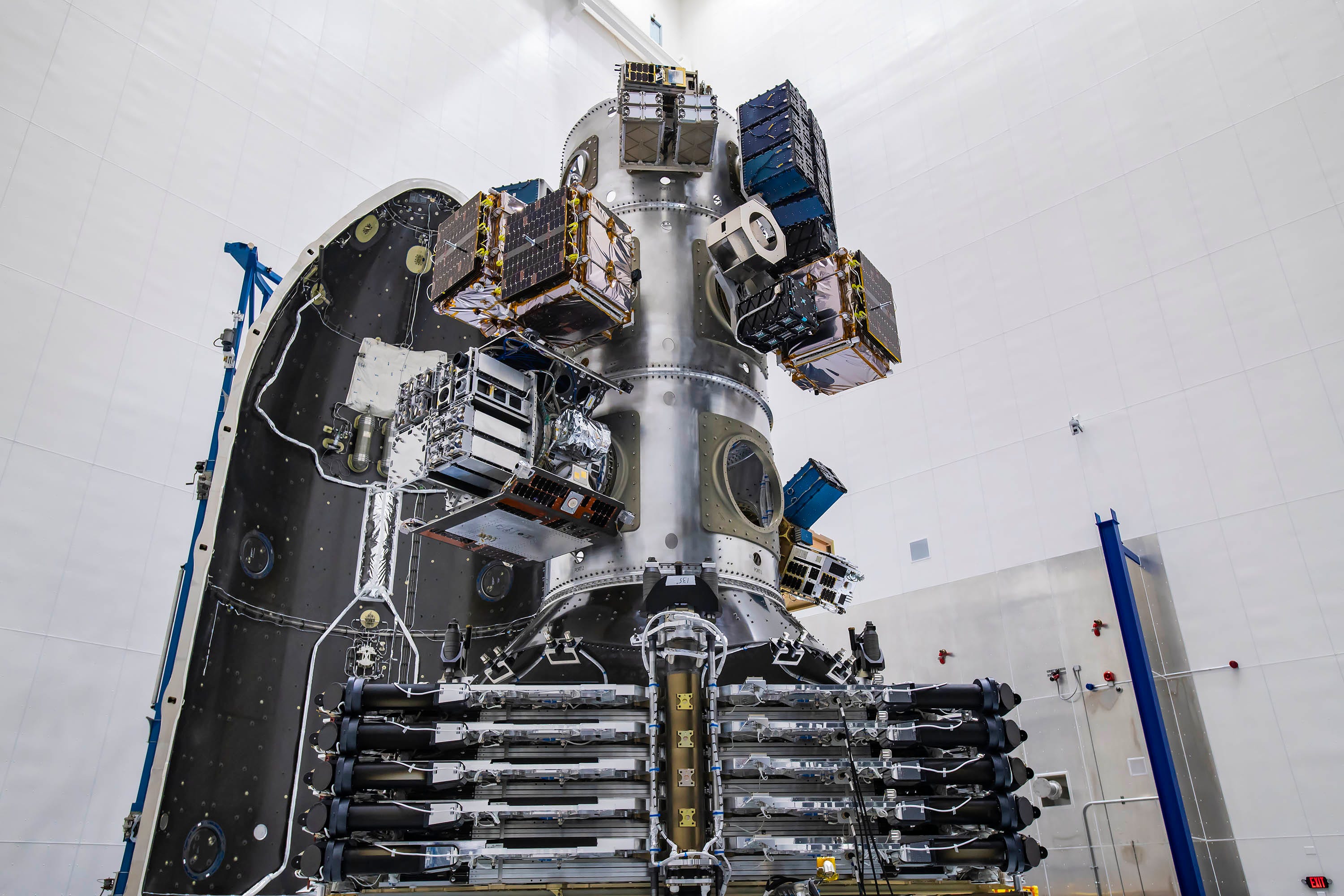

If you haven’t seen pictures of the 143 satellites fitting together like some sort of Escheresque jigsaw, you should. So here it is, courtesy of SpaceX’s Twitter feed:

As a side note, just read some of the comments...they are...well, they are comments. They are reminiscent (unfortunately) of the genuinely bizarre questions Musk faced during his presentation at the 67th International Astronautical Congress in September 2016. About as odd as the stack of satellites in the picture above.

Let’s acknowledge that it is a crazy-looking stack. The fact that all satellites deployed successfully speaks to the Falcon 9’s versatility and capability. At least six companies (not all from the U.S.) are working as deployment outfitters, getting the 133 small satellites ready for the launch by placing them on deployers. More shocking, the satellite operators number about another 21 companies (not including Starlink). So, this single Transporter-1 launch served 27 smallsat-type businesses.

The various customer satellites add up to over 950 kilograms, which, if we take SpaceX’s advertised rideshare rate of $5,000 per kilogram, adds up to $4,750,000. That might help defray the cost of launching 10 Starlink satellites, totaling 2,600 kg (at least before SpaceX added on OISLs). But the 950 kg from client satellites is far short of the 5,000 kg some analysts believe is required to break even with launching a single Falcon 9. But it does add up if SpaceX keeps launching Rideshare rockets with equivalent numbers (or more) of customer satellites on board.

Launching nearly 1,000 kg of small satellites for that small amount of cash demonstrates SpaceX’s ability to compete with dedicated smallsat launch providers--Rocket Lab, Virgin Orbit, and Arianespace’s Vega--so long as satellite operators are satisfied with the Falcon 9’s destination. SpaceX’s price per kilogram is exceptionally competitive.

Note the 10 Starlink satellites formed the base of the stack. The deployer (which also deploys) was mounted on top of the Starlinks, which had small satellites or other satellite deployers directly attached. Those deployers could be fairly simple shells with springs to push cubesats away (the blue boxes on the top right of the deployer), or something that launches away from the deployer, then launching smallsats from that (like the Spaceflight Industries Sherpa FX sort of peeking from behind the right of the stack). That’s a deployer on a deployer on top of a deployer?

All of the satellites ejected successfully from the deployer (the central column). You can witness it on Youtube--go towards the end. The stack of Starlinks deployed from the second stage after the deployment of all 133 satellites.

It appears SpaceX is conducting its Rideshare program in earnest. Earlier versions had two or three customer satellites mounted to a plate on top of a much larger stack of Starlink satellites. But the Transporter-1 launch demonstrates the company has gone through the trouble of creating a dedicated deployer designed to mount on top of a smaller Starlink stack. A commercial company doesn’t build something like that for a single mission. It wouldn’t be shocking if SpaceX eventually comes clean with the story that it has XX of those deployers ready to go for future Rideshare-focused missions.

Starlink’s Coherent Communications

Now turning to the laser crosslinks (OISLs) on the Starlink satellites Musk revealed in his tweet. If you’re curious about what they look like, they are those black corner caps on the satellites--seen in the stack pictured above (Musk confirmed that in the same tweet-stream). There’s not much information out there right now about how much more mass those crosslinks add to Starlink’s satellite bus. And, of course, there’s no information about the costs of those OISL modules (although they may cost more than an entire Starlink satellite).

The seemingly carefree addition of those OISLs to the Starlink bus demonstrates its “plug-and-play” nature. SpaceX appears to easily add/trade different satellite payloads to the Starlink bus without too much trouble. This is good news for the Space Development Agency, which awarded SpaceX a contract for four satellites. The fact there are now Starlink satellites with OISLs is a bonus for the SDA contract, too, since optical crosslinks are also required. I’ve already written an analysis on how the SDA’s contract with SpaceX may be a glimpse of a future in which low-cost satellites, delivered on schedule, are the rule for DoD acquisitions--and not the exception they are today.

To be clear, the ten Starlinks with OISLs deployed a few days ago will not provide much capability to the current constellation. Just one orbital plane and single inclination provides a string of north/south satellites with the ability to pass data from the ground to each other, but no other Starlink satellites. It’s not clear if ten satellites even allows the data to complete an orbital “circuit.” But, like so many other SpaceX activities, that will change quickly and the OISLs will become useful to subscribers beyond the constellation’s current limitations.

SpaceX will require fewer ground stations than its competitors once the company deploys OISL Starlinks broadly. This development opens up markets that OneWeb won’t be able to address for some time. Broadband connectivity between Starlink and transoceanic flights and cruises will be possible by 2022. Polar coverage may be available sooner since SpaceX is deploying OISL Starlinks in polar orbit this year. SpaceX will likely have different terminals to appeal to each of those transportation sectors. The questions for Starlink adoption in those areas will be around reliability and pricing. Can SpaceX provide products (terminals) and services for less than those offered from companies like SES?

Of course, a few military organizations might be interested in Starlink as another satellite communications option as well. Such DoD experimentation, and likely acceptance, may not bode well for legacy communication satellite manufacturers charging high prices.

SpaceX’s partnership with Microsoft’s Azure Space and its Modular Datacenters (MDC) makes much more sense when OISLs are part of Starlink. With an honest-to-goodness low-latency broadband connection from space, Microsoft could place an MDC nearly anywhere on the planet--perhaps including in places where the DoD is operating. That’s an interesting capability with potential that the DoD hasn’t inexpensively explored. Without OISLs, SpaceX’s Starlink competitors cannot field the same ability.

OISLs are also bad news for Starlink’s competition as SpaceX moves LEO broadband performance goalposts--again.

OneWeb is still recovering from its bankruptcy and the pandemic’s impact. Its current satellites are manufactured on a bus that carries limited mass, possibly limited enough to disallow the addition of OISLs. So, for OneWeb to provide a comparable service, it will need to redesign a new generation--which may take the company some time. It certainly doesn’t have the cash for a redesign--OneWeb is still courting other investors to help get the company over the initial layout hump.

Telesat is moving slowly, possibly hoping for more government investment. The company is targeting government and businesses as potential customers for its constellation. It may be designing the most fantastic satellite ever, but SpaceX’s constant iteration puts Telesat at a disadvantage if the customers experience SpaceX’s service first. Amazon’s also-deliberate pace with its satellite constellation may work against it as SpaceX keeps changing the rules. The company has already complained to the FCC about how SpaceX’s changing business plans are, astonishingly, not considering Amazon’s slow-moving plans.

I wonder if brick and mortar bookstores lodged similar complaints when Amazon ate all their lunches?

Comments ()